AI orchestration patterns

When we talk about AI orchestration, most of the time what we’re really referring to is agent orchestration; composing agentic applications where the agents are part of a larger unit trying to achieve some goal.

In many AI frameworks and libraries, it’s common to see agents make calls directly to other agents. There are new protocols popping up every day to facilitate agent communications like the Agent-to-Agent protocol (A2A), Agent Communication Protocol (ACP), and the Model Context Protocol (MCP) which supports tools that might be involved in a larger agentic orchestration.

It can be tempting for agents to make calls directly to other agents. It certainly makes it easier to build sample applications. The problem is that sample applications that make design compromises aren’t really ready for production.

Flexible composition is key

Let’s assume that we’re making an activity recommendation application that has multiple agents, some of which may be called concurrently while others are called sequentially. In this application, we have a weather agent and an activity agent. The weather agent retrieves the weather forecast for when the user wants to plan an activity, and then supplies that forecast to the activity agent.

In most samples, including the pattern designs by Microsoft that are discussed in this post, the weather agent will make a direct call to the activity agent. This may seem like an obvious choice, but it has lasting consequences for long-term development.

If one agent is coded to directly call another agent, then that agent must always call that other agent. In the scenario just described, the weather agent will always call the activity agent, making it difficult (if not impossible) to reuse the weather agent in other flows within the same application.

The way Akka approaches this problem is through workflows and best practices in building composable systems. Agents built with Akka typically do exactly one thing, and ideally this one thing is small. These small building block agents lend themselves well to being composed in different ways to support multiple patterns.

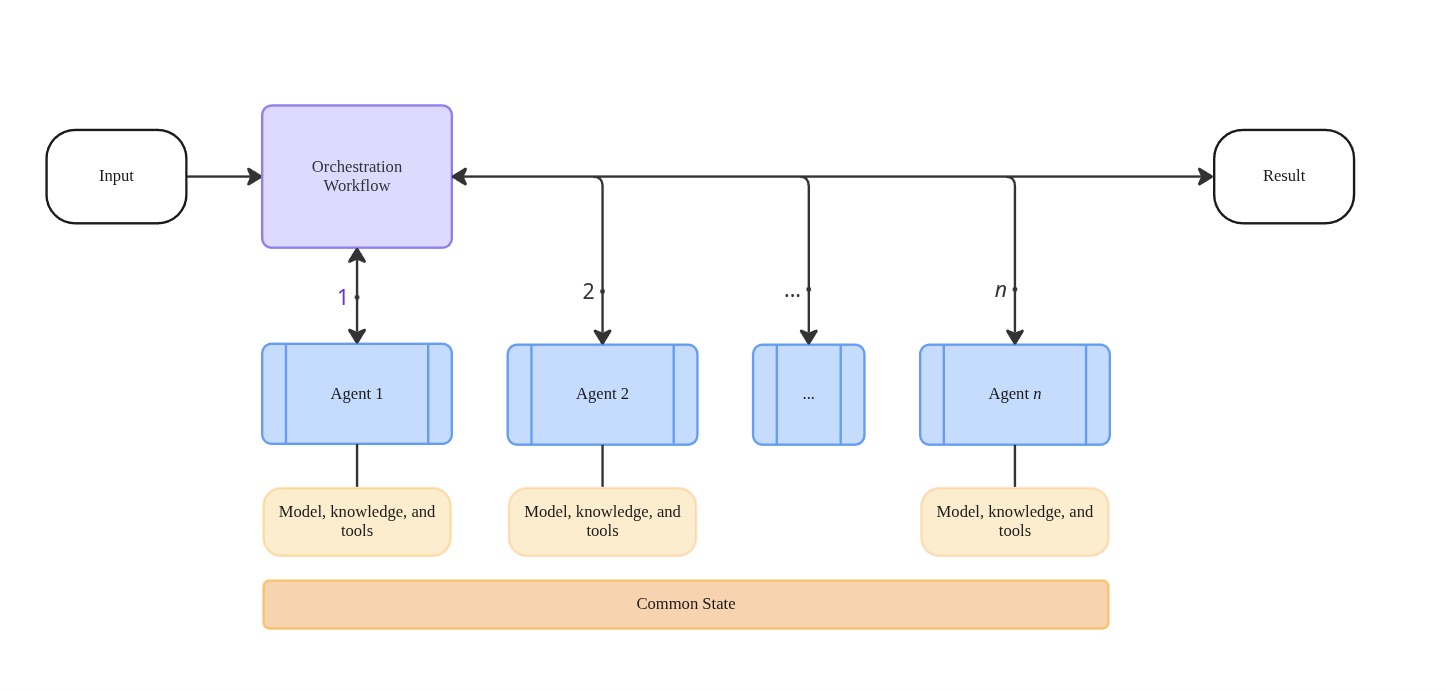

The key difference between direct agent communication and Akka’s approach is that in Akka the workflow makes the decision as to which agents are called, when they’re called, and if they’re called concurrently. Agents then become small, easily managed pieces of code to manage discrete interactions with a model. The results of those interactions can be reused in many different ways by the guiding workflows.

This orchestration approach is often called the supervisor pattern: a central workflow acts as the supervisor, coordinating multiple worker agents. Agents don’t communicate directly with each other—instead, the supervisor decides which agents to call, in what order, and how to handle their outputs. This separation keeps agents simple and reusable while centralizing reliability concerns like durable execution steps, retries, and failure handling in the workflow.

The rest of this document goes through all of Microsoft’s agent design patterns and illustrates how that pattern can be accomplished using Akka’s components.

Sequential orchestration

In the sequential orchestration pattern, AI agents are assembled in linear chains (also frequently referred to as “pipelines”) in a well-known, fixed order at development time. Each agent in the chain passes the output of its work to the input of the next agent in the chain.

Akka moves the responsibility of direct agent calls up to an orchestrating workflow, as shown in this adaptation of the original pattern:

This pattern is used in step-by-step processing, where each step builds on the results of the previous step.

Sequential orchestration is ideal for:

-

Multi-step processes with clear linear dependencies and a workflow progression that doesn’t change between runs

-

Data transformation pipelines (though if the only thing you’re doing is data transformation, agents and LLMs may not be necessary)

-

Steps that cannot be executed concurrently

You should avoid sequential orchestration when:

-

Steps are embarrassingly parallel. When it’s clear that these things can be run without downstream dependencies, you should instead use concurrent orchestration.

-

When you might need to branch or short-circuit the workflow based on results from individual steps

-

Agent interaction is more like collaboration than sequential hand-offs

Examples

-

In this example, this pattern is illustrated well with a workflow with deterministic steps (no dynamic planning) that calls agents in sequence

Concurrent orchestration

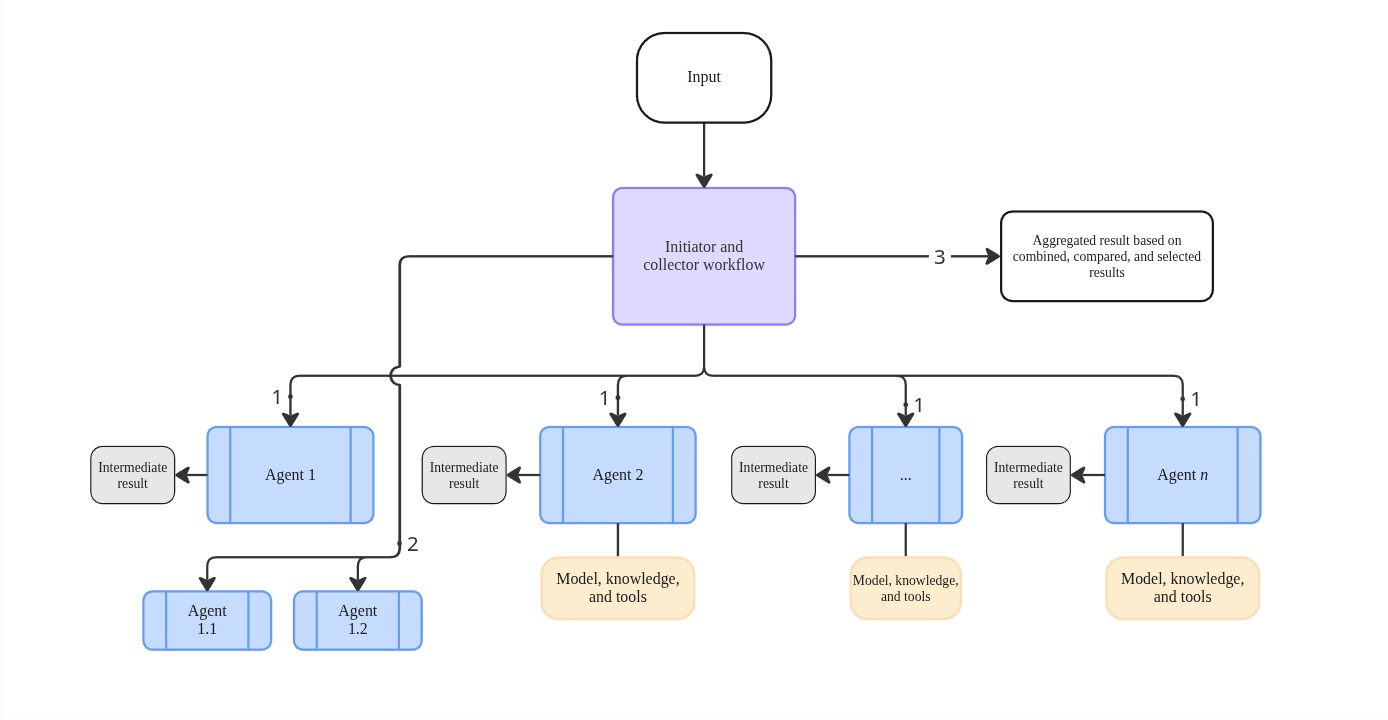

Concurrent orchestration refers to running multiple AI agents simultaneously working on the same task. The outputs of all concurrent agents are then collected and processed. This is ideal when you have a number of agentic tasks that do not rely on the outputs of others.

In Microsoft’s original diagram, there is an “Initiator and collector agent.” In the Akka version, we’ve simply replaced the collector agent with a workflow. Nearly everything else remains the same.

Also note that in this diagram, the workflow is responsible for controlling agent 1.1 and agent 1.2, which appear as sub-agents in Microsoft’s pattern. In keeping with the golden rule of agentic composition, Akka agents don’t spawn sub-agents, workflows decide which agents are needed and the Akka runtime takes care of provisioning.

As you’ll see later in this document, Akka workflows can easily spawn concurrent agents or even sub-workflows as needed. This reinforces the notion that the only real difference between these patterns in Akka and elsewhere is that Akka separates the roles of orchestration and model communication while most other frameworks choose to combine them.

More advanced concurrent orchestration could be implemented by a parent workflow spawning child workflows. In this pattern, each child workflow performs a multi-step task and then delivers the result back to the parent workflow as a message (i.e. method call). The parent workflow pauses when waiting for the results from children. The results would be stored in the state, and when the parent workflow is satisfied with all of the collected results it transitions to another step.

In this kind of advanced scenario, Akka takes care of all the hard parts like managing distributed state, distributed long-running timers, workflow resiliency, and much more.

Examples

The following code snippet shows how easily we can create a workflow step that calls two agents concurrently and gathers their results to be passed to the next step in the workflow:

private StepEffect askWeatherAndTraffic() throws Exception {

// call WeatherAgent and TrafficAgent in parallel

var forecastCall = componentClient

.forAgent()

.inSession(sessionId())

.method(WeatherAgent::query)

.invokeAsync(currentState().userQuery); (1)

var trafficAlertsCall = componentClient

.forAgent()

.inSession(sessionId())

.method(TrafficAgent::query)

.invokeAsync(currentState().userQuery); (1)

// collect the results

var forecast = forecastCall.toCompletableFuture().get(30, TimeUnit.SECONDS); (2)

var trafficAlerts = trafficAlertsCall.toCompletableFuture().get(30, TimeUnit.SECONDS); (2)

return stepEffects()

.updateState(currentState().withWeather(forecast).withTraffic(trafficAlerts))

.thenTransitionTo(ConcurrentWorkflow::suggestActivities); (3)

}| 1 | Call the WeatherAgent and TrafficAgent with invokeAsync, which immediately returns a CompletionStage of the future result. |

| 2 | Collect the results from the two agents. |

| 3 | Update the workflow state and continue with next step. |

Group chat orchestration

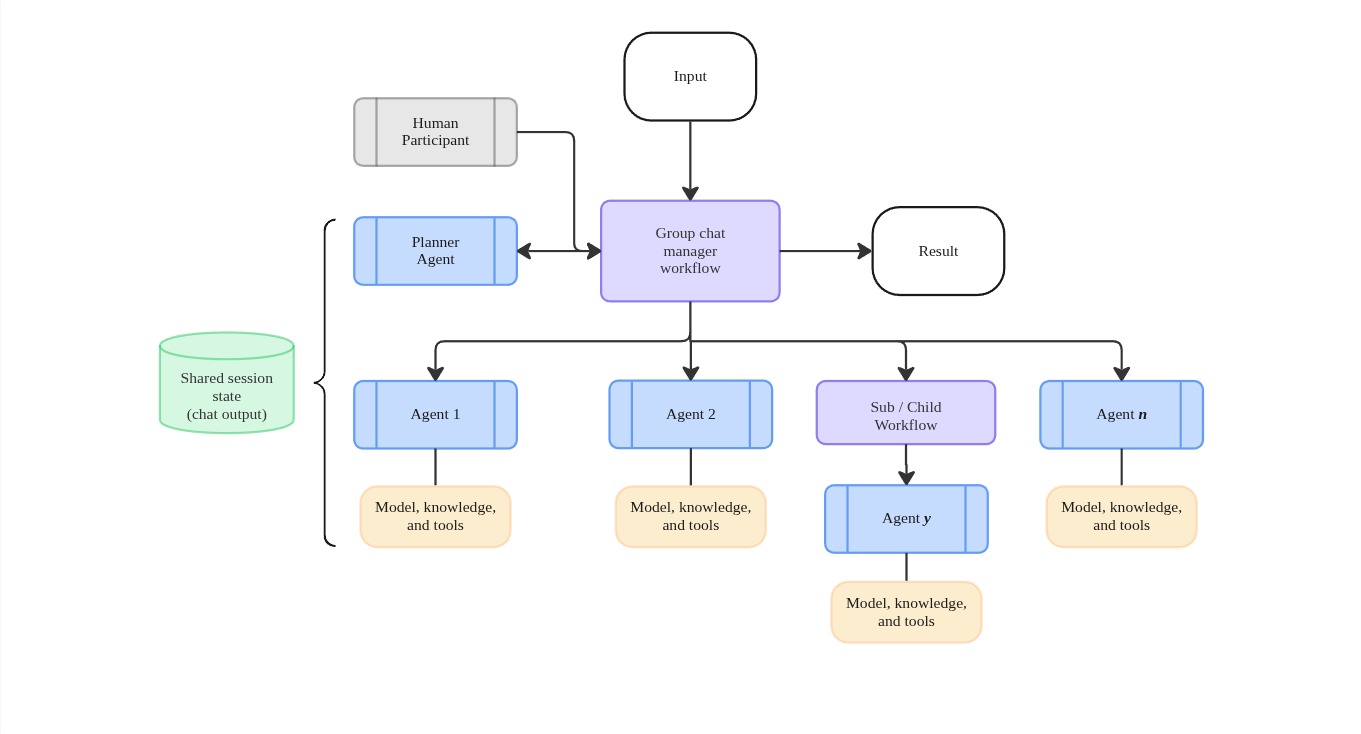

Group chat orchestration is when multiple agents collaborate to solve problems, make decisions, or judge work products. This collaboration between agents is facilitated by a shared discussion and a chat manager to coordinate all of the activities.

Calling this pattern a group “chat” can be misleading. We prefer to use a more generalized pattern name, such as shared sessions where multiple agents have different levels of access to a common conversation history during the task. Group chat is just one of many possible implementations of this pattern.

In this example, the parent workflow calls a planner agent. The planner agent’s job is to interact with a model to determine an execution plan and then return this plan as some well-typed, structured data.

This plan is then interpreted and followed by the parent workflow, which then delegates to agents and even child workflows. Throughout all of these agent and workflow interactions, a common shared session is used by all of the agents when building context for LLMs.

This concept of a shared session in Akka is flexible enough that it can be applied to any of the patterns outlined in this document.

Group chat (session) orchestration is ideal for:

-

Collaborative scenarios between agents, workflows, and sub-workflows

-

Validation and quality control where evaluation and quality checks can be done based on the session history

Group chat (session) orchestration should be avoided when:

-

A sequential pipeline is enough to accomplish the goal

-

Conversations that grow rapidly without upper limits can tax applications and infrastructure and when there are extreme numbers of chat sessions within short periods of time

-

There is no objective way to examine data and determine when a conversation is complete

Examples

The main piece of functionality that makes group chat style patterns work is the ability for agents to share sessions. In Akka, session access is incredibly robust, allowing some agents read-only, others write-only, and yet others read-and-write access.

Here are just a few sample applications that make use of explicit sessions via the inSession function on the agent client builder:

-

ask-akka-agent - An agentic conversation sample

-

multi-agent - Our classic multi-agent sample

-

trip-agent - A trip planning agent

Handoff orchestration

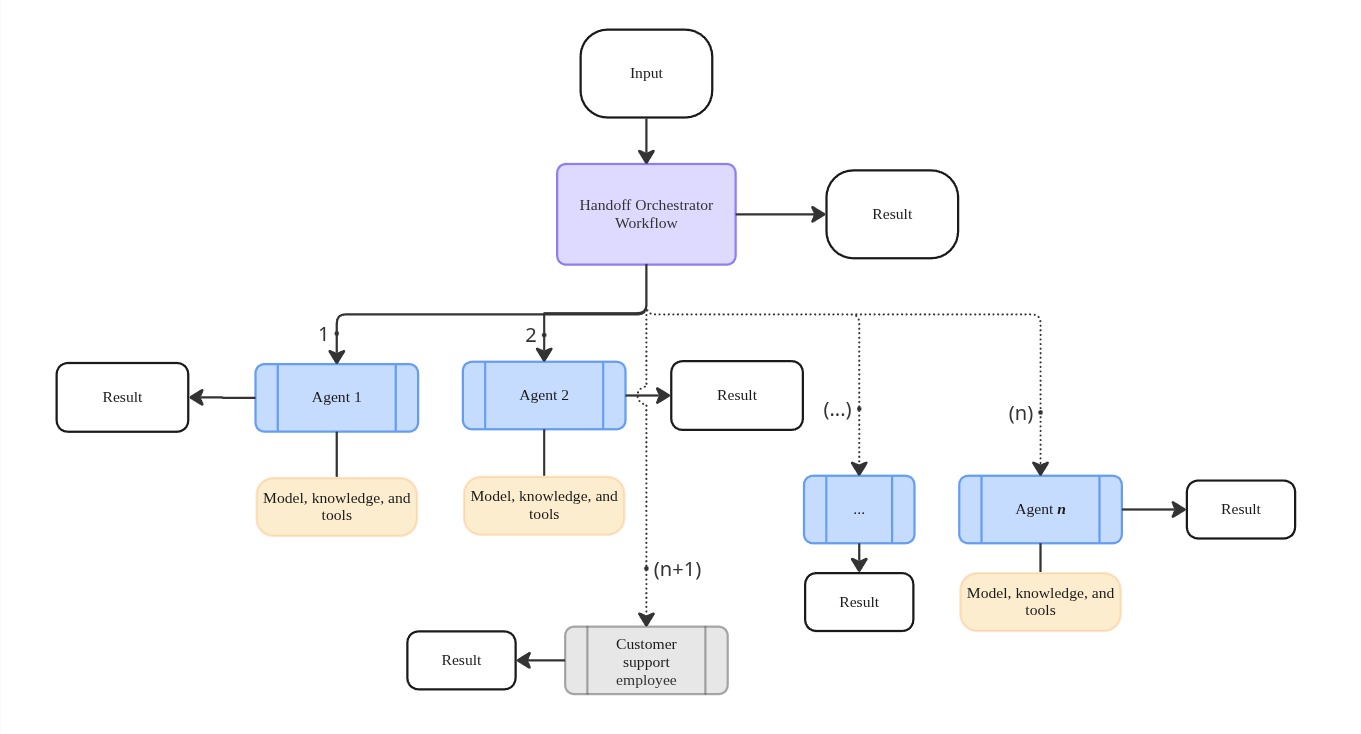

Handoff orchestration refers to empowering agents to defer or to hand off work to some other part of the process. In this pattern the plan and tasks are not completely known until receiving the initial input. Part of the dynamic planning process involves choosing which agents will be involved and which will not.

Akka views the use of “handoffs” as a specialization of the standard orchestration workflow available within Akka supporting dynamic, runtime planning and execution involving dynamic agents and tools.

If the individual agents are responsible for deciding if they’re going to handle a given input or instruction, then those agents can’t be recomposed for any other purpose. With Akka, you can use a combination of workflows, optional sub-workflows, and specialized planning agents.

With agents getting structured responses from LLMs, it is possible to instruct the LLM to judge what agent might be best suited for handling a request. The planning response is then handled by the workflow, which calls the selected agent.

Tool calls (e.g. MCP) can be used to add more deterministic logic to planning and routing when pure LLM-based judgment might not be predictable enough.

This plan-and-execute loop can be extended by combining it with any of the other patterns outlined in this document.

Examples

The PlannerAgent in this example illustrates this pattern.

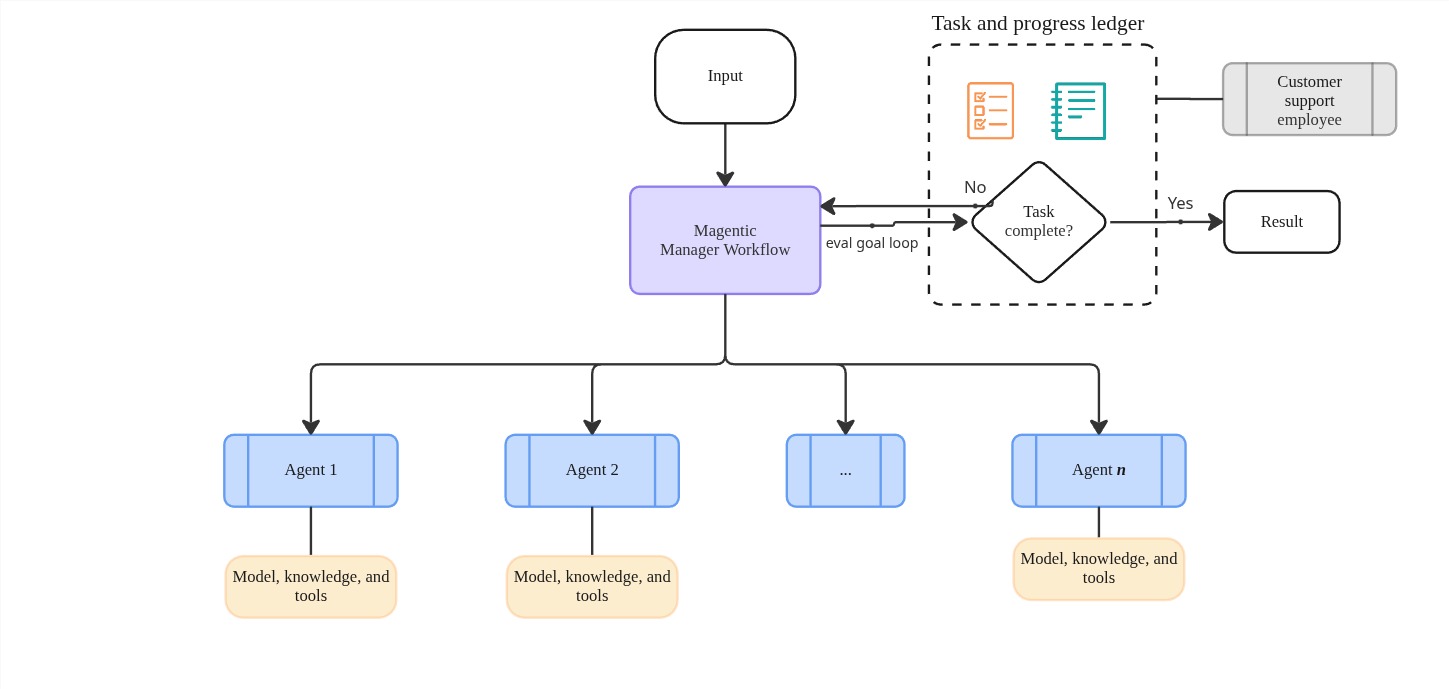

Magentic orchestration

Magentic orchestration is a pattern for open-ended, complex problems that don’t have a predetermined plan. This dynamic planning aspect often overlaps with other patterns in this group. In this pattern, agents frequently have access to tools.

While the origin of the term magentic is open for debate, our best guess for the origin of this word is that it’s a portmanteau of “multi-agent agentic” or “multi-agentic”.

In this dynamic variant of the supervisor pattern, an AI model creates the plan, decides the next step, evaluates results, and determines when the goal has been achieved. The workflow still provides durable execution with built-in retry mechanisms—the AI influences what happens, but the workflow ensures it happens reliably.

When we use workflows as ubiquitous coordinators and allow agents to be small, purpose-built model interaction components, then the need for individual, concrete patterns becomes less explicit. We don’t need to rewrite agents if we want to use them in different ways, we can either change how planning agents work or modify small bits of logic in the workflow.

Examples

In our Akka dynamic orchestration example, we illustrate a planning and evaluation loop, as well as re-planning.

Additionally, the Akka adaptive multi-agent sample implements the MagenticOne pattern.