New to Akka? Start with the Akka SDK.

Classic Supervision

This chapter outlines the concept behind the supervision in Akka Classic, for the corresponding overview of the new APIs see supervision

What Supervision Means

Supervision describes a dependency relationship between actors: the supervisor delegates tasks to subordinates and therefore must respond to their failures. When a subordinate detects a failure (i.e. throws an exception), it suspends itself and all its subordinates and sends a message to its supervisor, signaling failure. Depending on the nature of the work to be supervised and the nature of the failure, the supervisor has a choice of the following four options:

- Resume the subordinate, keeping its accumulated internal state

- Restart the subordinate, clearing out its accumulated internal state

- Stop the subordinate permanently

- Escalate the failure, thereby failing itself

It is important to always view an actor as part of a supervision hierarchy, which explains the existence of the fourth choice (as a supervisor also is subordinate to another supervisor higher up) and has implications on the first three: resuming an actor resumes all its subordinates, restarting an actor entails restarting all its subordinates (but see below for more details), similarly terminating an actor will also terminate all its subordinates. It should be noted that the default behavior of the preRestart hook of the Actor class is to terminate all its children before restarting, but this hook can be overridden; the recursive restart applies to all children left after this hook has been executed.

Each supervisor is configured with a function translating all possible failure causes (i.e. exceptions) into one of the four choices given above; notably, this function does not take the failed actor’s identity as an input. It is quite easy to come up with examples of structures where this might not seem flexible enough, e.g. wishing for different strategies to be applied to different subordinates. At this point, it is vital to understand that supervision is about forming a recursive fault handling structure. If you try to do too much at one level, it will become hard to reason about, hence the recommended way, in this case, is to add a level of supervision.

Akka implements a specific form called “parental supervision”. Actors can only be created by other actors—where the top-level actor is provided by the library—and each created actor is supervised by its parent. This restriction makes the formation of actor supervision hierarchies implicit and encourages sound design decisions. It should be noted that this also guarantees that actors cannot be orphaned or attached to supervisors from the outside, which might otherwise catch them unawares. Besides, this yields a natural and clean shutdown procedure for (sub-trees of) actor applications.

Supervision-related communication happens by special system messages that have their mailboxes separate from user messages. This implies that supervision related events are not deterministically ordered relative to ordinary messages. In general, the user cannot influence the order of normal messages and failure notifications. For details and example see the Discussion: Message Ordering section.

The Top-Level Supervisors

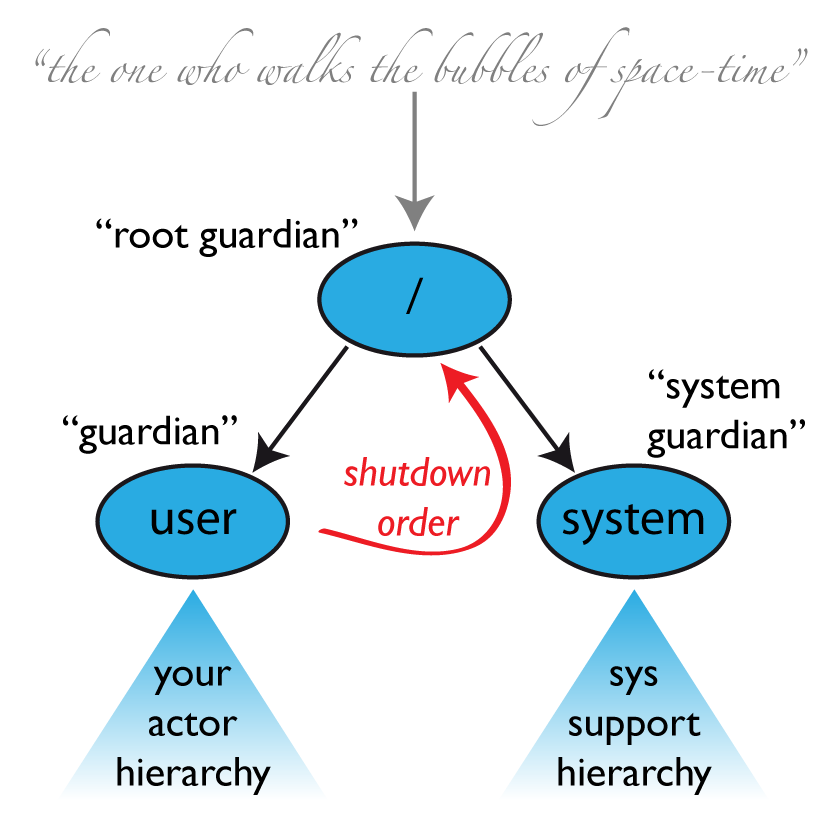

An actor system will during its creation start at least three actors, shown in the image above. For more information about the consequences for actor paths see Top-Level Scopes for Actor Paths.

/user: The Guardian Actor

The actor which is probably most interacted with is the parent of all user-created actors, the guardian named "/user". Actors created using system.actorOf() are children of this actor. This means that when this guardian terminates, all normal actors in the system will be shutdown, too. It also means that this guardian’s supervisor strategy determines how the top-level normal actors are supervised. Since Akka 2.1 it is possible to configure this using the setting akka.actor.guardian-supervisor-strategy, which takes the fully-qualified class-name of a SupervisorStrategyConfigurator. When the guardian escalates a failure, the root guardian’s response will be to terminate the guardian, which in effect will shut down the whole actor system.

/system: The System Guardian

This special guardian has been introduced to achieve an orderly shut-down sequence where logging remains active while all normal actors terminate, even though logging itself is implemented using actors. This is realized by having the system guardian watch the user guardian and initiate its shut-down upon reception of the Terminated message. The top-level system actors are supervised using a strategy which will restart indefinitely upon all types of Exception except for ActorInitializationException and ActorKilledException, which will terminate the child in question. All other throwables are escalated, which will shut down the whole actor system.

/: The Root Guardian

The root guardian is the grand-parent of all so-called “top-level” actors and supervises all the special actors mentioned in Top-Level Scopes for Actor Paths using the SupervisorStrategy.stoppingStrategy, whose purpose is to terminate the child upon any type of Exception. All other throwables will be escalated … but to whom? Since every real actor has a supervisor, the supervisor of the root guardian cannot be a real actor. And because this means that it is “outside of the bubble”, it is called the “bubble-walker”. This is a synthetic ActorRef which in effect stops its child upon the first sign of trouble and sets the actor system’s isTerminated status to true as soon as the root guardian is fully terminated (all children recursively stopped).

One-For-One Strategy vs. All-For-One Strategy

There are two classes of supervision strategies which come with Akka: OneForOneStrategy and AllForOneStrategy. Both are configured with a mapping from exception type to supervision directive (see above) and limits on how often a child is allowed to fail before terminating it. The difference between them is that the former applies the obtained directive only to the failed child, whereas the latter applies it to all siblings as well. Normally, you should use the OneForOneStrategy, which also is the default if none is specified explicitly.

The AllForOneStrategy is applicable in cases where the ensemble of children has such tight dependencies among them, that a failure of one child affects the function of the others, i.e. they are inextricably linked. Since a restart does not clear out the mailbox, it often is best to terminate the children upon failure and re-create them explicitly from the supervisor (by watching the children’s lifecycle); otherwise, you have to make sure that it is no problem for any of the actors to receive a message which was queued before the restart but processed afterwards.

Normally stopping a child (i.e. not in response to a failure) will not automatically terminate the other children in an all-for-one strategy; this can be done by watching their lifecycle: if the Terminated message is not handled by the supervisor, it will throw a DeathPactException which (depending on its supervisor) will restart it, and the default preRestart action will terminate all children. Of course, this can be handled explicitly as well.

Please note that creating one-off actors from an all-for-one supervisor entails that failures escalated by the temporary actor will affect all the permanent ones. If this is not desired, install an intermediate supervisor; this can very be done by declaring a router of size 1 for the worker, see Routing.