New to Akka? Start with the Akka SDK.

Schema Evolution for Event Sourced Actors

Dependency

The Akka dependencies are available from Akka’s secure library repository. To access them you need to use a secure, tokenized URL as specified at https://account.akka.io/token.

This documentation page touches upon Akka Persistence, so to follow those examples you will want to depend on:

- sbt

val AkkaVersion = "2.10.16" libraryDependencies ++= Seq( "com.typesafe.akka" %% "akka-persistence" % AkkaVersion, "com.typesafe.akka" %% "akka-persistence-testkit" % AkkaVersion % Test )- Maven

<properties> <scala.binary.version>2.13</scala.binary.version> </properties> <dependencyManagement> <dependencies> <dependency> <groupId>com.typesafe.akka</groupId> <artifactId>akka-bom_${scala.binary.version}</artifactId> <version>2.10.16</version> <type>pom</type> <scope>import</scope> </dependency> </dependencies> </dependencyManagement> <dependencies> <dependency> <groupId>com.typesafe.akka</groupId> <artifactId>akka-persistence_${scala.binary.version}</artifactId> </dependency> <dependency> <groupId>com.typesafe.akka</groupId> <artifactId>akka-persistence-testkit_${scala.binary.version}</artifactId> <scope>test</scope> </dependency> </dependencies>- Gradle

def versions = [ ScalaBinary: "2.13" ] dependencies { implementation platform("com.typesafe.akka:akka-bom_${versions.ScalaBinary}:2.10.16") implementation "com.typesafe.akka:akka-persistence_${versions.ScalaBinary}" testImplementation "com.typesafe.akka:akka-persistence-testkit_${versions.ScalaBinary}" }

Introduction

When working on long running projects using Persistence, or any kind of Event Sourcing architectures, schema evolution becomes one of the more important technical aspects of developing your application. The requirements as well as our own understanding of the business domain may (and will) change in time.

In fact, if a project matures to the point where you need to evolve its schema to adapt to changing business requirements you can view this as first signs of its success – if you wouldn’t need to adapt anything over an apps lifecycle that could mean that no-one is really using it actively.

In this chapter we will investigate various schema evolution strategies and techniques from which you can pick and choose the ones that match your domain and challenge at hand.

This page proposes a number of possible solutions to the schema evolution problem and explains how some of the utilities Akka provides can be used to achieve this, it is by no means a complete (closed) set of solutions.

Sometimes, based on the capabilities of your serialization formats, you may be able to evolve your schema in different ways than outlined in the sections below. If you discover useful patterns or techniques for schema evolution feel free to submit Pull Requests to this page to extend it.

Schema evolution in event-sourced systems

In recent years we have observed a tremendous move towards immutable append-only datastores, with event-sourcing being the prime technique successfully being used in these settings. For an excellent overview why and how immutable data makes scalability and systems design much simpler you may want to read Pat Helland’s excellent Immutability Changes Everything whitepaper.

Since with Event Sourcing the events are immutable and usually never deleted – the way schema evolution is handled differs from how one would go about it in a mutable database setting (e.g. in typical CRUD database applications).

The system needs to be able to continue to work in the presence of “old” events which were stored under the “old” schema. We also want to limit complexity in the business logic layer, exposing a consistent view over all of the events of a given type to PersistentActorAbstractPersistentActor s and persistence queries. This allows the business logic layer to focus on solving business problems instead of having to explicitly deal with different schemas.

In summary, schema evolution in event sourced systems exposes the following characteristics:

- Allow the system to continue operating without large scale migrations to be applied,

- Allow the system to read “old” events from the underlying storage, however present them in a “new” view to the application logic,

- Transparently promote events to the latest versions during recovery (or queries) such that the business logic need not consider multiple versions of events

Types of schema evolution

Before we explain the various techniques that can be used to safely evolve the schema of your persistent events over time, we first need to define what the actual problem is, and what the typical styles of changes are.

Since events are never deleted, we need to have a way to be able to replay (read) old events, in such way that does not force the PersistentActorAbstractPersistentActor to be aware of all possible versions of an event that it may have persisted in the past. Instead, we want the Actors to work on some form of “latest” version of the event and provide some means of either converting old “versions” of stored events into this “latest” event type, or constantly evolve the event definition - in a backwards compatible way - such that the new deserialization code can still read old events.

The most common schema changes you will likely are:

- adding a field to an event type,

- remove or rename field in event type,

- remove event type,

- split event into multiple smaller events.

The following sections will explain some patterns which can be used to safely evolve your schema when facing those changes.

Picking the right serialization format

Picking the serialization format is a very important decision you will have to make while building your application. It affects which kind of evolutions are simple (or hard) to do, how much work is required to add a new datatype, and, last but not least, serialization performance.

If you find yourself realising you have picked “the wrong” serialization format, it is always possible to change the format used for storing new events, however you would have to keep the old deserialization code in order to be able to replay events that were persisted using the old serialization scheme. It is possible to “rebuild” an event-log from one serialization format to another one, however it may be a more involved process if you need to perform this on a live system.

Serialization with Jackson is a good choice in many cases and our recommendation if you don’t have other preference. It also has support for Schema Evolution.

Google Protocol Buffers is good if you want more control over the schema evolution of your messages, but it requires more work to develop and maintain the mapping between serialized representation and domain representation.

Binary serialization formats that we have seen work well for long-lived applications include the very flexible IDL based: Google Protocol Buffers, Apache Thrift or Apache Avro. Avro schema evolution is more “entire schema” based, instead of single fields focused like in protobuf or thrift, and usually requires using some kind of schema registry.

There are plenty excellent blog posts explaining the various trade-offs between popular serialization formats, one post we would like to highlight is the very well illustrated Schema evolution in Avro, Protocol Buffers and Thrift by Martin Kleppmann.

Provided default serializers

Akka Persistence provides Google Protocol Buffers based serializers (using Akka Serialization) for its own message types such as PersistentReprPersistentRepr, AtomicWriteAtomicWrite and snapshots. Journal plugin implementations may choose to use those provided serializers, or pick a serializer which suits the underlying database better.

Serialization is NOT handled automatically by Akka Persistence itself. Instead, it only provides the above described serializers, and in case a AsyncWriteJournalAsyncWriteJournal plugin implementation chooses to use them directly, the above serialization scheme will be used.

Please refer to your write journal’s documentation to learn more about how it handles serialization!

For example, some journals may choose to not use Akka Serialization at all and instead store the data in a format that is more “native” for the underlying datastore, e.g. using JSON or some other kind of format that the target datastore understands directly.

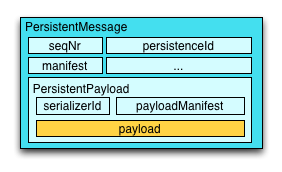

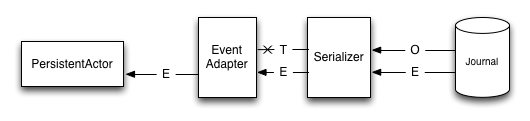

The below figure explains how the default serialization scheme works, and how it fits together with serializing the user provided message itself, which we will from here on refer to as the payload (highlighted in yellow):

Akka Persistence provided serializers wrap the user payload in an envelope containing all persistence-relevant information. If the Journal uses provided Protobuf serializers for the wrapper types (e.g. PersistentRepr), then the payload will be serialized using the user configured serializer, and if none is provided explicitly, Java serialization will be used for it.

The blue colored regions of the PersistentMessage indicate what is serialized using the generated protocol buffers serializers, and the yellow payload indicates the user provided event (by calling persist(payload)(...)persist(payload,...). As you can see, the PersistentMessage acts as an envelope around the payload, adding various fields related to the origin of the event (persistenceId, sequenceNr and more).

More advanced techniques (e.g. Remove event class and ignore events) will dive into using the manifests for increasing the flexibility of the persisted vs. exposed types even more. However for now we will focus on the simpler evolution techniques, concerning only configuring the payload serializers.

By default the payload will be serialized using Java Serialization. This is fine for testing and initial phases of your development (while you’re still figuring out things, and the data will not need to stay persisted forever). However, once you move to production you should really pick a different serializer for your payloads.

Do not rely on Java serialization for serious application development! It does not lean itself well to evolving schemas over long periods of time, and its performance is also not very high (it never was designed for high-throughput scenarios).

Configuring payload serializers

This section aims to highlight the complete basics on how to define custom serializers using Akka Serialization. Many journal plugin implementations use Akka Serialization, thus it is tremendously important to understand how to configure it to work with your event classes.

Read the Akka Serialization docs to learn more about defining custom serializers.

The below snippet explains in the minimal amount of lines how a custom serializer can be registered. For more in-depth explanations on how serialization picks the serializer to use etc, please refer to its documentation.

First we start by defining our domain model class, here representing a person:

- Scala

-

source

final case class Person(name: String, surname: String) - Java

-

source

static class Person { public final String name; public final String surname; public Person(String name, String surname) { this.name = name; this.surname = surname; } }

Next we implement a serializer (or extend an existing one to be able to handle the new Person class):

- Scala

-

source

/** * Simplest possible serializer, uses a string representation of the Person class. * * Usually a serializer like this would use a library like: * protobuf, kryo, avro, cap'n proto, flatbuffers, SBE or some other dedicated serializer backend * to perform the actual to/from bytes marshalling. */ class SimplestPossiblePersonSerializer extends SerializerWithStringManifest { val Utf8 = Charset.forName("UTF-8") val PersonManifest = classOf[Person].getName // unique identifier of the serializer def identifier = 1234567 // extract manifest to be stored together with serialized object override def manifest(o: AnyRef): String = o.getClass.getName // serialize the object override def toBinary(obj: AnyRef): Array[Byte] = obj match { case p: Person => s"""${p.name}|${p.surname}""".getBytes(Utf8) case _ => throw new IllegalArgumentException(s"Unable to serialize to bytes, clazz was: ${obj.getClass}!") } // deserialize the object, using the manifest to indicate which logic to apply override def fromBinary(bytes: Array[Byte], manifest: String): AnyRef = manifest match { case PersonManifest => val nameAndSurname = new String(bytes, Utf8) val Array(name, surname) = nameAndSurname.split("[|]") Person(name, surname) case _ => throw new NotSerializableException( s"Unable to deserialize from bytes, manifest was: $manifest! Bytes length: " + bytes.length) } } - Java

-

source

/** * Simplest possible serializer, uses a string representation of the Person class. * * <p>Usually a serializer like this would use a library like: protobuf, kryo, avro, cap'n * proto, flatbuffers, SBE or some other dedicated serializer backend to perform the actual * to/from bytes marshalling. */ static class SimplestPossiblePersonSerializer extends SerializerWithStringManifest { private final Charset utf8 = StandardCharsets.UTF_8; private final String personManifest = Person.class.getName(); // unique identifier of the serializer @Override public int identifier() { return 1234567; } // extract manifest to be stored together with serialized object @Override public String manifest(Object o) { return o.getClass().getName(); } // serialize the object @Override public byte[] toBinary(Object obj) { if (obj instanceof Person) { Person p = (Person) obj; return (p.name + "|" + p.surname).getBytes(utf8); } else { throw new IllegalArgumentException( "Unable to serialize to bytes, clazz was: " + obj.getClass().getName()); } } // deserialize the object, using the manifest to indicate which logic to apply @Override public Object fromBinary(byte[] bytes, String manifest) throws NotSerializableException { if (personManifest.equals(manifest)) { String nameAndSurname = new String(bytes, utf8); String[] parts = nameAndSurname.split("[|]"); return new Person(parts[0], parts[1]); } else { throw new NotSerializableException( "Unable to deserialize from bytes, manifest was: " + manifest + "! Bytes length: " + bytes.length); } } }

And finally we register the serializer and bind it to handle the docs.persistence.Person class:

source# application.conf

akka {

actor {

serializers {

person = "docs.persistence.SimplestPossiblePersonSerializer"

}

serialization-bindings {

"docs.persistence.Person" = person

}

}

}

Deserialization will be performed by the same serializer which serialized the message initially because of the identifier being stored together with the message.

Please refer to the Akka Serialization documentation for more advanced use of serializers, especially the Serializer with String Manifest section since it is very useful for Persistence based applications dealing with schema evolutions, as we will see in some of the examples below.

Schema evolution in action

In this section we will discuss various schema evolution techniques using concrete examples and explaining some of the various options one might go about handling the described situation. The list below is by no means a complete guide, so feel free to adapt these techniques depending on your serializer’s capabilities and/or other domain specific limitations.

Serialization with Jackson has good support for Schema Evolution and many of the scenarios described here can be solved with that Jackson transformation technique instead.

Add fields

Situation: You need to add a field to an existing message type. For example, a SeatReserved(letter:String, row:Int)SeatReserved(String letter, int row) now needs to have an associated code which indicates if it is a window or aisle seat.

Solution: Adding fields is the most common change you’ll need to apply to your messages so make sure the serialization format you picked for your payloads can handle it appropriately, i.e. such changes should be binary compatible. This is achieved using the right serializer toolkit. In the following examples we will be using protobuf. See also how to add fields with Jackson.

While being able to read messages with missing fields is half of the solution, you also need to deal with the missing values somehow. This is usually modeled as some kind of default value, or by representing the field as an Option[T]Optional<T> See below for an example how reading an optional field from a serialized protocol buffers message might look like.

- Scala

-

source

sealed abstract class SeatType { def code: String } object SeatType { def fromString(s: String) = s match { case Window.code => Window case Aisle.code => Aisle case Other.code => Other case _ => Unknown } case object Window extends SeatType { override val code = "W" } case object Aisle extends SeatType { override val code = "A" } case object Other extends SeatType { override val code = "O" } case object Unknown extends SeatType { override val code = "" } } case class SeatReserved(letter: String, row: Int, seatType: SeatType) - Java

-

source

static enum SeatType { Window("W"), Aisle("A"), Other("O"), Unknown(""); private final String code; private SeatType(String code) { this.code = code; } public static SeatType fromCode(String c) { if (Window.code.equals(c)) return Window; else if (Aisle.code.equals(c)) return Aisle; else if (Other.code.equals(c)) return Other; else return Unknown; } } static class SeatReserved { public final String letter; public final int row; public final SeatType seatType; public SeatReserved(String letter, int row, SeatType seatType) { this.letter = letter; this.row = row; this.seatType = seatType; } }

Next we prepare a protocol definition using the protobuf Interface Description Language, which we’ll use to generate the serializer code to be used on the Akka Serialization layer (notice that the schema approach allows us to rename fields, as long as the numeric identifiers of the fields do not change):

source// FlightAppModels.proto

option java_package = "docs.persistence.proto";

option optimize_for = SPEED;

message SeatReserved {

required string letter = 1;

required uint32 row = 2;

optional string seatType = 3; // the new field

}

The serializer implementation uses the protobuf generated classes to marshall the payloads. Optional fields can be handled explicitly or missing values by calling the has... methods on the protobuf object, which we do for seatType in order to use a Unknown type in case the event was stored before we had introduced the field to this event type:

- Scala

-

source

/** * Example serializer impl which uses protocol buffers generated classes (proto.*) * to perform the to/from binary marshalling. */ class AddedFieldsSerializerWithProtobuf extends SerializerWithStringManifest { override def identifier = 67876 final val SeatReservedManifest = classOf[SeatReserved].getName override def manifest(o: AnyRef): String = o.getClass.getName override def fromBinary(bytes: Array[Byte], manifest: String): AnyRef = manifest match { case SeatReservedManifest => // use generated protobuf serializer seatReserved(FlightAppModels.SeatReserved.parseFrom(bytes)) case _ => throw new NotSerializableException("Unable to handle manifest: " + manifest) } override def toBinary(o: AnyRef): Array[Byte] = o match { case s: SeatReserved => FlightAppModels.SeatReserved.newBuilder .setRow(s.row) .setLetter(s.letter) .setSeatType(s.seatType.code) .build() .toByteArray } // -- fromBinary helpers -- private def seatReserved(p: FlightAppModels.SeatReserved): SeatReserved = SeatReserved(p.getLetter, p.getRow, seatType(p)) // handle missing field by assigning "Unknown" value private def seatType(p: FlightAppModels.SeatReserved): SeatType = if (p.hasSeatType) SeatType.fromString(p.getSeatType) else SeatType.Unknown } - Java

-

source

/** * Example serializer impl which uses protocol buffers generated classes (proto.*) to perform the * to/from binary marshalling. */ static class AddedFieldsSerializerWithProtobuf extends SerializerWithStringManifest { @Override public int identifier() { return 67876; } private final String seatReservedManifest = SeatReserved.class.getName(); @Override public String manifest(Object o) { return o.getClass().getName(); } @Override public Object fromBinary(byte[] bytes, String manifest) throws NotSerializableException { if (seatReservedManifest.equals(manifest)) { // use generated protobuf serializer try { return seatReserved(FlightAppModels.SeatReserved.parseFrom(bytes)); } catch (InvalidProtocolBufferException e) { throw new IllegalArgumentException(e.getMessage()); } } else { throw new NotSerializableException("Unable to handle manifest: " + manifest); } } @Override public byte[] toBinary(Object o) { if (o instanceof SeatReserved) { SeatReserved s = (SeatReserved) o; return FlightAppModels.SeatReserved.newBuilder() .setRow(s.row) .setLetter(s.letter) .setSeatType(s.seatType.code) .build() .toByteArray(); } else { throw new IllegalArgumentException("Unable to handle: " + o); } } // -- fromBinary helpers -- private SeatReserved seatReserved(FlightAppModels.SeatReserved p) { return new SeatReserved(p.getLetter(), p.getRow(), seatType(p)); } // handle missing field by assigning "Unknown" value private SeatType seatType(FlightAppModels.SeatReserved p) { if (p.hasSeatType()) return SeatType.fromCode(p.getSeatType()); else return SeatType.Unknown; } }

Rename fields

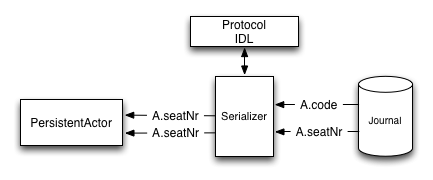

Situation: When first designing the system the SeatReserved event featured a code field. After some time you discover that what was originally called code actually means seatNr, thus the model should be changed to reflect this concept more accurately.

Solution 1 - using IDL based serializers: First, we will discuss the most efficient way of dealing with such kinds of schema changes – IDL based serializers.

IDL stands for Interface Description Language, and means that the schema of the messages that will be stored is based on this description. Most IDL based serializers also generate the serializer / deserializer code so that using them is not too hard. Examples of such serializers are protobuf or thrift.

Using these libraries rename operations are “free”, because the field name is never actually stored in the binary representation of the message. This is one of the advantages of schema based serializers, even though that they add the overhead of having to maintain the schema. When using serializers like this, no additional code change (except renaming the field and method used during serialization) is needed to perform such evolution:

This is how such a rename would look in protobuf:

source// protobuf message definition, BEFORE:

message SeatReserved {

required string code = 1;

}

// protobuf message definition, AFTER:

message SeatReserved {

required string seatNr = 1; // field renamed, id remains the same

}

It is important to learn about the strengths and limitations of your serializers, in order to be able to move swiftly and refactor your models fearlessly as you go on with the project.

Learn in-depth about the serialization engine you’re using as it will impact how you can approach schema evolution.

Some operations are “free” in certain serialization formats (more often than not: removing/adding optional fields, sometimes renaming fields etc.), while some other operations are strictly not possible.

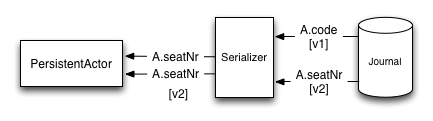

Solution 2 - by manually handling the event versions: Another solution, in case your serialization format does not support renames like the above mentioned formats, is versioning your schema. For example, you could have made your events carry an additional field called _version which was set to 1 (because it was the initial schema), and once you change the schema you bump this number to 2, and write an adapter which can perform the rename.

This approach is popular when your serialization format is something like JSON, where renames can not be performed automatically by the serializer. See also how to rename fields with Jackson, which is using this kind of versioning approach.

The following snippet showcases how one could apply renames if working with plain JSON (using spray.json.JsObjecta JsObject as an example JSON representation):

- Scala

-

source

class JsonRenamedFieldAdapter extends EventAdapter { val marshaller = new ExampleJsonMarshaller val V1 = "v1" val V2 = "v2" // this could be done independently for each event type override def manifest(event: Any): String = V2 override def toJournal(event: Any): JsObject = marshaller.toJson(event) override def fromJournal(event: Any, manifest: String): EventSeq = event match { case json: JsObject => EventSeq(marshaller.fromJson(manifest match { case V1 => rename(json, "code", "seatNr") case V2 => json // pass-through case unknown => throw new IllegalArgumentException(s"Unknown manifest: $unknown") })) case _ => val c = event.getClass throw new IllegalArgumentException("Can only work with JSON, was: %s".format(c)) } def rename(json: JsObject, from: String, to: String): JsObject = { val value = json.fields(from) val withoutOld = json.fields - from JsObject(withoutOld + (to -> value)) } } - Java

-

source

static class JsonRenamedFieldAdapter implements EventAdapter { // use your favorite json library private final ExampleJsonMarshaller marshaller = new ExampleJsonMarshaller(); private final String V1 = "v1"; private final String V2 = "v2"; // this could be done independently for each event type @Override public String manifest(Object event) { return V2; } @Override public JsObject toJournal(Object event) { return marshaller.toJson(event); } @Override public EventSeq fromJournal(Object event, String manifest) { if (event instanceof JsObject) { JsObject json = (JsObject) event; if (V1.equals(manifest)) json = rename(json, "code", "seatNr"); return EventSeq.single(json); } else { throw new IllegalArgumentException( "Can only work with JSON, was: " + event.getClass().getName()); } } private JsObject rename(JsObject json, String from, String to) { // use your favorite json library to rename the field JsObject renamed = json; return renamed; } }

As you can see, manually handling renames induces some boilerplate onto the EventAdapter, however much of it you will find is common infrastructure code that can be either provided by an external library (for promotion management) or put together in a simple helper traitclass.

The technique of versioning events and then promoting them to the latest version using JSON transformations can be applied to more than just field renames – it also applies to adding fields and all kinds of changes in the message format.

Remove event class and ignore events

Situation: While investigating app performance you notice that unreasonable amounts of CustomerBlinked events are being stored for every customer each time he/she blinks. Upon investigation, you decide that the event does not add any value and should be deleted. You still have to be able to replay from a journal which contains those old CustomerBlinked events though.

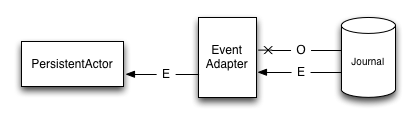

Naive solution - drop events in EventAdapter:

The problem of removing an event type from the domain model is not as much its removal, as the implications for the recovery mechanisms that this entails. For example, a naive way of filtering out certain kinds of events from being delivered to a recovering PersistentActor is pretty simple, as one can filter them out in an EventAdapter:

The EventAdapterEventAdapter can drop old events (**O**) by emitting an empty EventSeqEventSeq. Other events can be passed through (**E**).

This however does not address the underlying cost of having to deserialize all the events during recovery, even those which will be filtered out by the adapter. In the next section we will improve the above explained mechanism to avoid deserializing events which would be filtered out by the adapter anyway, thus allowing to save precious time during a recovery containing lots of such events (without actually having to delete them).

Improved solution - deserialize into tombstone:

In the just described technique we have saved the PersistentActor from receiving un-wanted events by filtering them out in the EventAdapterEventAdapter, however the event itself still was deserialized and loaded into memory. This has two notable downsides:

- first, that the deserialization was actually performed, so we spent some of our time budget on the deserialization, even though the event does not contribute anything to the persistent actors state.

- second, that we are unable to remove the event class from the system – since the serializer still needs to create the actual instance of it, as it does not know it will not be used.

The solution to these problems is to use a serializer that is aware of that event being no longer needed, and can notice this before starting to deserialize the object.

This approach allows us to remove the original class from our classpath, which makes for less “old” classes lying around in the project. This can for example be implemented by using an SerializerWithStringManifestSerializerWithStringManifest (documented in depth in Serializer with String Manifest). By looking at the string manifest, the serializer can notice that the type is no longer needed, and skip the deserialization all-together:

The serializer is aware of the old event types that need to be skipped (**O**), and can skip deserializing them altogether by returning a “tombstone” (**T**), which the EventAdapter converts into an empty EventSeq. Other events (**E**) can just be passed through.

The serializer detects that the string manifest points to a removed event type and skips attempting to deserialize it:

- Scala

-

source

case object EventDeserializationSkipped class RemovedEventsAwareSerializer extends SerializerWithStringManifest { val utf8 = Charset.forName("UTF-8") override def identifier: Int = 8337 val SkipEventManifestsEvents = Set("docs.persistence.CustomerBlinked" // ... ) override def manifest(o: AnyRef): String = o.getClass.getName override def toBinary(o: AnyRef): Array[Byte] = o match { case _ => o.toString.getBytes(utf8) // example serialization } override def fromBinary(bytes: Array[Byte], manifest: String): AnyRef = manifest match { case m if SkipEventManifestsEvents.contains(m) => EventDeserializationSkipped case _ => new String(bytes, utf8) } } - Java

-

source

static class EventDeserializationSkipped { public static EventDeserializationSkipped instance = new EventDeserializationSkipped(); private EventDeserializationSkipped() {} } static class RemovedEventsAwareSerializer extends SerializerWithStringManifest { private final Charset utf8 = StandardCharsets.UTF_8; private final String customerBlinkedManifest = "blinked"; // unique identifier of the serializer @Override public int identifier() { return 8337; } // extract manifest to be stored together with serialized object @Override public String manifest(Object o) { if (o instanceof CustomerBlinked) return customerBlinkedManifest; else return o.getClass().getName(); } @Override public byte[] toBinary(Object o) { return o.toString().getBytes(utf8); // example serialization } @Override public Object fromBinary(byte[] bytes, String manifest) { if (customerBlinkedManifest.equals(manifest)) return EventDeserializationSkipped.instance; else return new String(bytes, utf8); } }

The EventAdapter we implemented is aware of EventDeserializationSkipped events (our “Tombstones”), and emits and empty EventSeq whenever such object is encountered:

- Scala

-

source

class SkippedEventsAwareAdapter extends EventAdapter { override def manifest(event: Any) = "" override def toJournal(event: Any) = event override def fromJournal(event: Any, manifest: String) = event match { case EventDeserializationSkipped => EventSeq.empty case _ => EventSeq(event) } } - Java

-

source

static class SkippedEventsAwareAdapter implements EventAdapter { @Override public String manifest(Object event) { return ""; } @Override public Object toJournal(Object event) { return event; } @Override public EventSeq fromJournal(Object event, String manifest) { if (event == EventDeserializationSkipped.instance) return EventSeq.empty(); else return EventSeq.single(event); } }

Detach domain model from data model

Situation: You want to separate the application model (often called the “domain model”) completely from the models used to persist the corresponding events (the “data model”). For example because the data representation may change independently of the domain model.

Another situation where this technique may be useful is when your serialization tool of choice requires generated classes to be used for serialization and deserialization of objects, like for example Google Protocol Buffers do, yet you do not want to leak this implementation detail into the domain model itself, which you’d like to model as plain Scala caseJava classes.

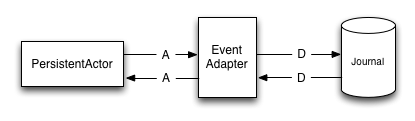

Solution: In order to detach the domain model, which is often represented using pure Scala (case)Java classes, from the data model classes which very often may be less user-friendly yet highly optimised for throughput and schema evolution (like the classes generated by protobuf for example), it is possible to use a simple EventAdapter which maps between these types in a 1:1 style as illustrated below:

Domain events (**A**) are adapted to the data model events (**D**) by the EventAdapter. The data model can be a format natively understood by the journal, such that it can store it more efficiently or include additional data for the event (e.g. tags), for ease of later querying.

We will use the following domain and data models to showcase how the separation can be implemented by the adapter:

- Scala

-

source

/** Domain model - highly optimised for domain language and maybe "fluent" usage */ object DomainModel { final case class Customer(name: String) final case class Seat(code: String) { def bookFor(customer: Customer): SeatBooked = SeatBooked(code, customer) } final case class SeatBooked(code: String, customer: Customer) } /** Data model - highly optimised for schema evolution and persistence */ object DataModel { final case class SeatBooked(code: String, customerName: String) } - Java

-

source

// Domain model - highly optimised for domain language and maybe "fluent" usage static class Customer { public final String name; public Customer(String name) { this.name = name; } } static class Seat { public final String code; public Seat(String code) { this.code = code; } public SeatBooked bookFor(Customer customer) { return new SeatBooked(code, customer); } } static class SeatBooked { public final String code; public final Customer customer; public SeatBooked(String code, Customer customer) { this.code = code; this.customer = customer; } } // Data model - highly optimised for schema evolution and persistence static class SeatBookedData { public final String code; public final String customerName; public SeatBookedData(String code, String customerName) { this.code = code; this.customerName = customerName; } }

The EventAdapterEventAdapter takes care of converting from one model to the other one (in both directions), allowing the models to be completely detached from each other, such that they can be optimised independently as long as the mapping logic is able to convert between them:

- Scala

-

source

class DetachedModelsAdapter extends EventAdapter { override def manifest(event: Any): String = "" override def toJournal(event: Any): Any = event match { case DomainModel.SeatBooked(code, customer) => DataModel.SeatBooked(code, customer.name) } override def fromJournal(event: Any, manifest: String): EventSeq = event match { case DataModel.SeatBooked(code, customerName) => EventSeq(DomainModel.SeatBooked(code, DomainModel.Customer(customerName))) } } - Java

-

source

class DetachedModelsAdapter implements EventAdapter { @Override public String manifest(Object event) { return ""; } @Override public Object toJournal(Object event) { if (event instanceof SeatBooked) { SeatBooked s = (SeatBooked) event; return new SeatBookedData(s.code, s.customer.name); } else { throw new IllegalArgumentException("Unsupported: " + event.getClass()); } } @Override public EventSeq fromJournal(Object event, String manifest) { if (event instanceof SeatBookedData) { SeatBookedData d = (SeatBookedData) event; return EventSeq.single(new SeatBooked(d.code, new Customer(d.customerName))); } else { throw new IllegalArgumentException("Unsupported: " + event.getClass()); } } }

The same technique could also be used directly in the Serializer if the end result of marshalling is bytes. Then the serializer can simply convert the bytes do the domain object by using the generated protobuf builders.

Store events as human-readable data model

Situation: You want to keep your persisted events in a human-readable format, for example JSON.

Solution: This is a special case of the Detach domain model from data model pattern, and thus requires some co-operation from the Journal implementation to achieve this.

An example of a Journal which may implement this pattern is MongoDB, however other databases such as PostgreSQL and Cassandra could also do it because of their built-in JSON capabilities.

In this approach, the EventAdapterEventAdapter is used as the marshalling layer: it serializes the events to/from JSON. The journal plugin notices that the incoming event type is JSON (for example by performing a match on the incoming event) and stores the incoming object directly.

- Scala

-

source

class JsonDataModelAdapter extends EventAdapter { override def manifest(event: Any): String = "" val marshaller = new ExampleJsonMarshaller override def toJournal(event: Any): JsObject = marshaller.toJson(event) override def fromJournal(event: Any, manifest: String): EventSeq = event match { case json: JsObject => EventSeq(marshaller.fromJson(json)) case _ => throw new IllegalArgumentException("Unable to fromJournal a non-JSON object! Was: " + event.getClass) } } - Java

-

source

static class JsonDataModelAdapter implements EventAdapter { // use your favorite json library private final ExampleJsonMarshaller marshaller = new ExampleJsonMarshaller(); @Override public String manifest(Object event) { return ""; } @Override public JsObject toJournal(Object event) { return marshaller.toJson(event); } @Override public EventSeq fromJournal(Object event, String manifest) { if (event instanceof JsObject) { JsObject json = (JsObject) event; return EventSeq.single(marshaller.fromJson(json)); } else { throw new IllegalArgumentException( "Unable to fromJournal a non-JSON object! Was: " + event.getClass()); } } }

This technique only applies if the Akka Persistence plugin you are using provides this capability. Check the documentation of your favourite plugin to see if it supports this style of persistence.

If it doesn’t, you may want to skim the list of existing journal plugins, just in case some other plugin for your favourite datastore does provide this capability.

Alternative solution:

In fact, an AsyncWriteJournal implementation could natively decide to not use binary serialization at all, and always serialize the incoming messages as JSON - in which case the toJournal implementation of the EventAdapterEventAdapter would be an identity function, and the fromJournal would need to de-serialize messages from JSON.

If in need of human-readable events on the write-side of your application reconsider whether preparing materialized views using Persistence Query would not be an efficient way to go about this, without compromising the write-side’s throughput characteristics.

If indeed you want to use a human-readable representation on the write-side, pick a Persistence plugin that provides that functionality, or – implement one yourself.

Split large event into fine-grained events

Situation: While refactoring your domain events, you find that one of the events has become too large (coarse-grained) and needs to be split up into multiple fine-grained events.

Solution: Let us consider a situation where an event represents “user details changed”. After some time we discover that this event is too coarse, and needs to be split into “user name changed” and “user address changed”, because somehow users keep changing their usernames a lot and we’d like to keep this as a separate event.

The write side change is very simple, we persist UserNameChanged or UserAddressChanged depending on what the user actually intended to change (instead of the composite UserDetailsChanged that we had in version 1 of our model).

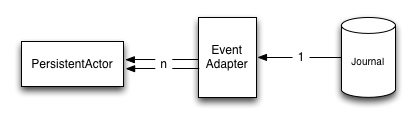

The EventAdapter splits the incoming event into smaller more fine-grained events during recovery.

During recovery however, we now need to convert the old V1 model into the V2 representation of the change. Depending if the old event contains a name change, we either emit the UserNameChanged or we don’t, and the address change is handled similarly:

- Scala

-

source

trait Version1 trait Version2 // V1 event: final case class UserDetailsChanged(name: String, address: String) extends Version1 // corresponding V2 events: final case class UserNameChanged(name: String) extends Version2 final case class UserAddressChanged(address: String) extends Version2 // event splitting adapter: class UserEventsAdapter extends EventAdapter { override def manifest(event: Any): String = "" override def fromJournal(event: Any, manifest: String): EventSeq = event match { case UserDetailsChanged(null, address) => EventSeq(UserAddressChanged(address)) case UserDetailsChanged(name, null) => EventSeq(UserNameChanged(name)) case UserDetailsChanged(name, address) => EventSeq(UserNameChanged(name), UserAddressChanged(address)) case event: Version2 => EventSeq(event) } override def toJournal(event: Any): Any = event } - Java

-

source

interface Version1 {}; interface Version2 {} // V1 event: static class UserDetailsChanged implements Version1 { public final String name; public final String address; public UserDetailsChanged(String name, String address) { this.name = name; this.address = address; } } // corresponding V2 events: static class UserNameChanged implements Version2 { public final String name; public UserNameChanged(String name) { this.name = name; } } static class UserAddressChanged implements Version2 { public final String address; public UserAddressChanged(String address) { this.address = address; } } // event splitting adapter: static class UserEventsAdapter implements EventAdapter { @Override public String manifest(Object event) { return ""; } @Override public EventSeq fromJournal(Object event, String manifest) { if (event instanceof UserDetailsChanged) { UserDetailsChanged c = (UserDetailsChanged) event; if (c.name == null) return EventSeq.single(new UserAddressChanged(c.address)); else if (c.address == null) return EventSeq.single(new UserNameChanged(c.name)); else return EventSeq.create(new UserNameChanged(c.name), new UserAddressChanged(c.address)); } else { return EventSeq.single(event); } } @Override public Object toJournal(Object event) { return event; } }

By returning an EventSeq from the event adapter, the recovered event can be converted to multiple events before being delivered to the persistent actor.