Getting Started Tutorial (Scala with Eclipse): First Chapter

Introduction

Welcome to the first tutorial on how to get started with Akka and Scala. We assume that you already know what Akka and Scala are and will now focus on the steps necessary to start your first project. We will be using Eclipse, and the Scala plugin for Eclipse.

The sample application that we will create is using actors to calculate the value of Pi. Calculating Pi is a CPU intensive operation and we will utilize Akka Actors to write a concurrent solution that scales out to multi-core processors. This sample will be extended in future tutorials to use Akka Remote Actors to scale out on multiple machines in a cluster.

We will be using an algorithm that is called “embarrassingly parallel” which just means that each job is completely isolated and not coupled with any other job. Since this algorithm is so parallelizable it suits the actor model very well.

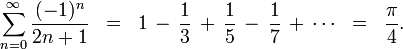

Here is the formula for the algorithm we will use:

In this particular algorithm the master splits the series into chunks which are sent out to each worker actor to be processed. When each worker has processed its chunk it sends a result back to the master which aggregates the total result.

Tutorial source code

If you want don’t want to type in the code and/or set up an SBT project then you can check out the full tutorial from the Akka GitHub repository. It is in the akka-tutorials/akka-tutorial-first module. You can also browse it online here, with the actual source code here.

Prerequisites

This tutorial assumes that you have Java 1.6 or later installed on you machine and java on your PATH. You also need to know how to run commands in a shell (ZSH, Bash, DOS etc.) and a recent version of Eclipse (at least 3.6 - Helios).

If you want to run the example from the command line as well, you need to make sure that $JAVA_HOME environment variable is set to the root of the Java distribution. You also need to make sure that the $JAVA_HOME/bin is on your PATH:

$ export JAVA_HOME=..root of java distribution..

$ export PATH=$PATH:$JAVA_HOME/bin

You can test your installation by invoking java:

$ java -version

java version "1.6.0_24"

Java(TM) SE Runtime Environment (build 1.6.0_24-b07-334-10M3326)

Java HotSpot(TM) 64-Bit Server VM (build 19.1-b02-334, mixed mode)

Downloading and installing Akka

To build and run the tutorial sample from the command line, you have to download Akka. If you prefer to use SBT to build and run the sample then you can skip this section and jump to the next one.

Let’s get the akka-actors-1.3.1.zip distribution of Akka from https://akka.io/downloads/ which includes everything we need for this tutorial. Once you have downloaded the distribution unzip it in the folder you would like to have Akka installed in. In my case I choose to install it in /Users/jboner/tools/, simply by unzipping it to this directory.

You need to do one more thing in order to install Akka properly: set the AKKA_HOME environment variable to the root of the distribution. In my case I’m opening up a shell, navigating down to the distribution, and setting the AKKA_HOME variable:

$ cd /Users/jboner/tools/akka-actors-1.3.1

$ export AKKA_HOME=`pwd`

$ echo $AKKA_HOME

/Users/jboner/tools/akka-actors-1.3.1

The distribution looks like this:

$ ls -1

config

doc

lib

src

- In the config directory we have the Akka conf files.

- In the doc directory we have the documentation, API, doc JARs, and also the source files for the tutorials.

- In the lib directory we have the Scala and Akka JARs.

- In the src directory we have the source JARs for Akka.

The only JAR we will need for this tutorial (apart from the scala-library.jar JAR) is the akka-actor-1.3.1.jar JAR in the lib/akka directory. This is a self-contained JAR with zero dependencies and contains everything we need to write a system using Actors.

Akka is very modular and has many JARs for containing different features. The core distribution has seven modules:

- akka-actor-1.3.1.jar – Standard Actors

- akka-typed-actor-1.3.1.jar – Typed Actors

- akka-remote-1.3.1.jar – Remote Actors

- akka-stm-1.3.1.jar – STM (Software Transactional Memory), transactors and transactional datastructures

- akka-http-1.3.1.jar – Akka Mist for continuation-based asynchronous HTTP and also Jersey integration

- akka-slf4j-1.3.1.jar – SLF4J Event Handler Listener for logging with SLF4J

- akka-testkit-1.3.1.jar – Toolkit for testing Actors

We also have Akka Modules containing add-on modules outside the core of Akka. You can download the Akka Modules distribution from https://akka.io/downloads/. It contains Akka core as well. We will not be needing any modules there today, but for your information the module JARs are these:

- akka-kernel-1.3.1.jar – Akka microkernel for running a bare-bones mini application server (embeds Jetty etc.)

- akka-amqp-1.3.1.jar – AMQP integration

- akka-camel-1.3.1.jar – Apache Camel Actors integration (it’s the best way to have your Akka application communicate with the rest of the world)

- akka-camel-typed-1.3.1.jar – Apache Camel Typed Actors integration

- akka-scalaz-1.3.1.jar – Support for the Scalaz library

- akka-spring-1.3.1.jar – Spring framework integration

- akka-osgi-dependencies-bundle-1.3.1.jar – OSGi support

Downloading and installing the Scala IDE for Eclipse

If you want to use Eclipse for coding your Akka tutorial, you need to install the Scala plugin for Eclipse. This plugin comes with its own version of Scala, so if you don’t plan to run the example from the command line, you don’t need to download the Scala distribution (and you can skip the next section).

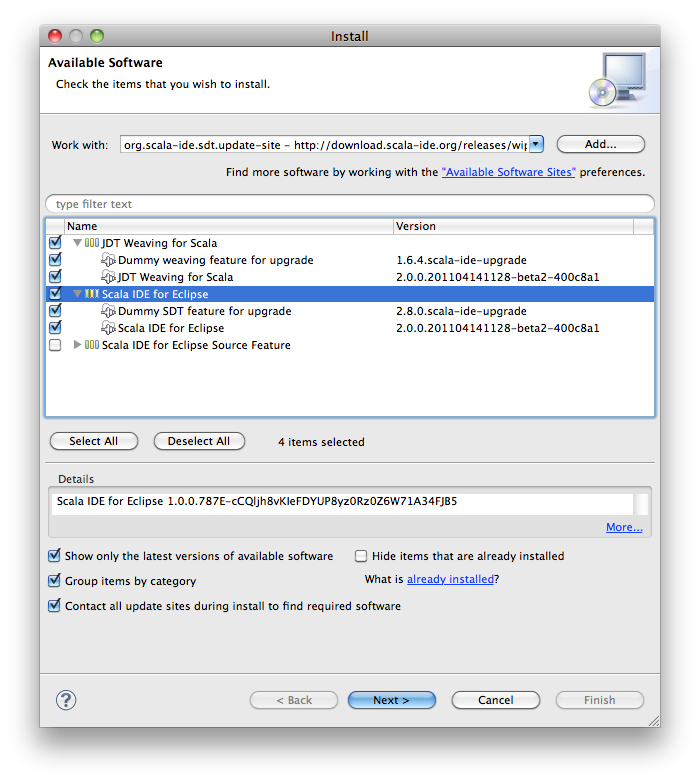

You can install this plugin using the regular update mechanism. First choose a version of the IDE from http://download.scala-ide.org. We recommend you choose 2.0.x, which comes with Scala 2.9. Copy the corresponding URL and then choose Help/Install New Software and paste the URL you just copied. You should see something similar to the following image.

Make sure you select both the JDT Weaving for Scala and the Scala IDE for Eclipse plugins. The other plugin is optional, and contains the source code of the plugin itself.

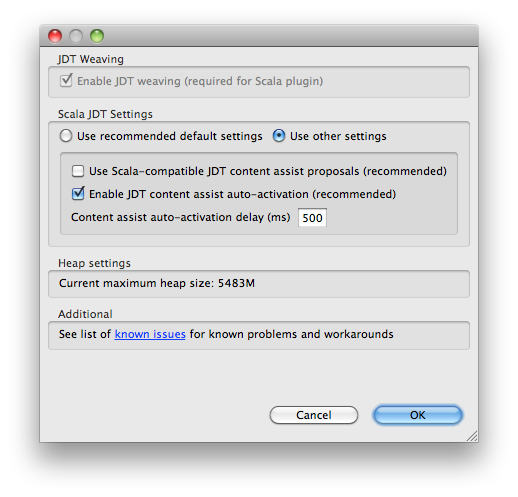

Once the installation is finished, you need to restart Eclipse. The first time the plugin starts it will open a diagnostics window and offer to fix several settings, such as the delay for content assist (code-completion) or the shown completion proposal types.

Accept the recommended settings, and follow the instructions if you need to increase the heap size of Eclipse.

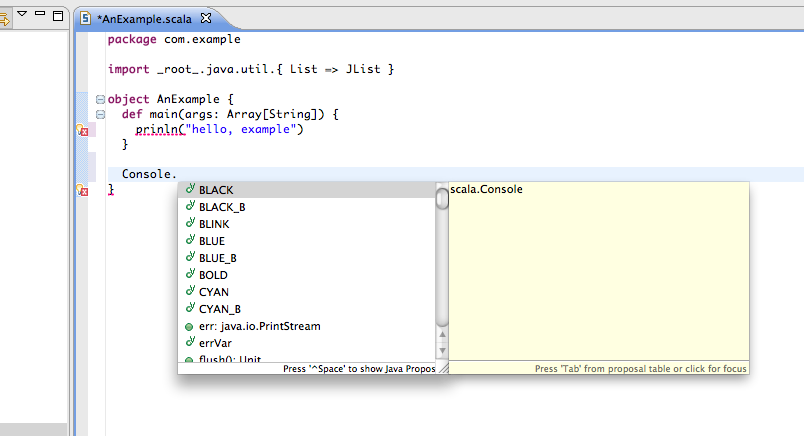

Check that the installation succeeded by creating a new Scala project (File/New>Scala Project), and typing some code. You should have content-assist, hyperlinking to definitions, instant error reporting, and so on.

You are ready to code now!

Downloading and installing Scala

To build and run the tutorial sample from the command line, you have to install the Scala distribution. If you prefer to use Eclipse to build and run the sample then you can skip this section and jump to the next one.

Scala can be downloaded from http://www.scala-lang.org/downloads. Browse there and download the Scala 2.9.1 release. If you pick the tgz or zip distribution then just unzip it where you want it installed. If you pick the IzPack Installer then double click on it and follow the instructions.

You also need to make sure that the scala-2.9.1/bin (if that is the directory where you installed Scala) is on your PATH:

$ export PATH=$PATH:scala-2.9.1/bin

You can test your installation by invoking scala:

$ scala -version

Scala code runner version 2.9.1.final -- Copyright 2002-2011, LAMP/EPFL

Looks like we are all good. Finally let’s create a source file Pi.scala for the tutorial and put it in the root of the Akka distribution in the tutorial directory (you have to create it first).

Some tools require you to set the SCALA_HOME environment variable to the root of the Scala distribution, however Akka does not require that.

Creating an Akka project in Eclipse

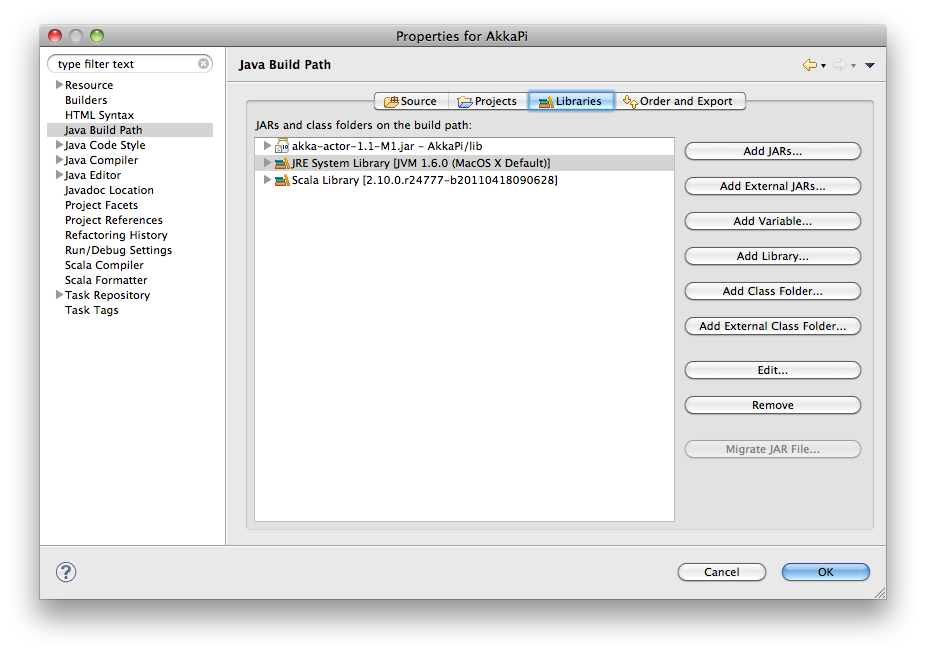

If you have not already done so, now is the time to create an Eclipse project for our tutorial. Use the New Scala Project wizard and accept the default settings. Once the project is open, we need to add the akka libraries to the build path. Right click on the project and choose Properties, then click on Java Build Path. Go to Libraries and click on Add External Jars.., then navigate to the location where you installed akka and choose akka-actor.jar. You should see something similar to this:

Using SBT in Eclipse

If you are an SBT user, you can follow the Downloading and installing SBT instruction and additionally install the sbteclipse plugin. This adds support for generating Eclipse project files from your SBT project. You need to install the plugin as described in the README of sbteclipse

Then run the eclipse target to generate the Eclipse project:

$ sbt

> eclipse

The options create-src and with-sources are useful:

$ sbt

> eclipse create-src with-sources

- create-src to create the common source directories, e.g. src/main/scala, src/main/test

- with-sources to create source attachments for the library dependencies

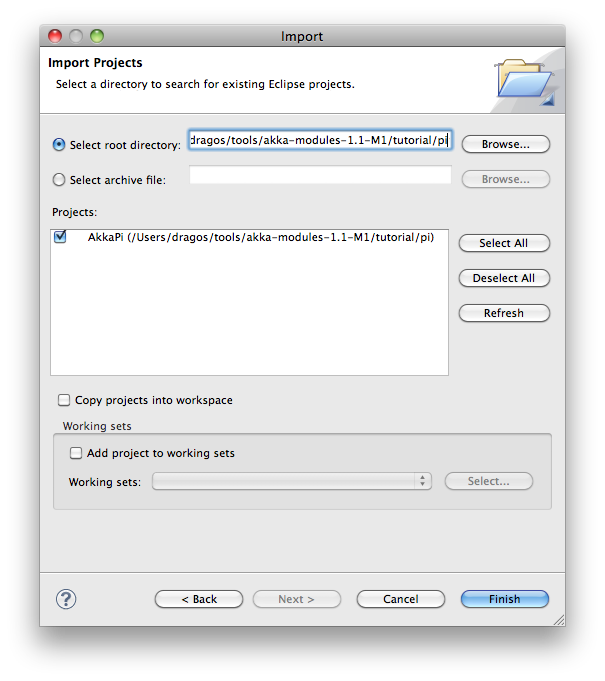

Next you need to import this project in Eclipse, by choosing Eclipse/Import.. Existing Projects into Workspace. Navigate to the directory where you defined your SBT project and choose import:

Now we have the basis for an Akka Eclipse application, so we can..

Start writing the code

The design we are aiming for is to have one Master actor initiating the computation, creating a set of Worker actors. Then it splits up the work into discrete chunks, and sends these chunks to the different workers in a round-robin fashion. The master waits until all the workers have completed their work and sent back results for aggregation. When computation is completed the master prints out the result, shuts down all workers and then itself.

With this in mind, let’s now create the messages that we want to have flowing in the system.

Creating the messages

We start by creating a package for our application, let’s call it akka.tutorial.first.scala. We start by creating case classes for each type of message in our application, so we can place them in a hierarchy, call it PiMessage. Right click on the package and choose New Scala Class, and enter PiMessage for the name of the class.

We need three different messages:

- Calculate – sent to the Master actor to start the calculation

- Work – sent from the Master actor to the Worker actors containing the work assignment

- Result – sent from the Worker actors to the Master actor containing the result from the worker’s calculation

Messages sent to actors should always be immutable to avoid sharing mutable state. In Scala we have ‘case classes’ which make excellent messages. So let’s start by creating three messages as case classes. We also create a common base trait for our messages (that we define as being sealed in order to prevent creating messages outside our control):

package akka.tutorial.first.scala

sealed trait PiMessage

case object Calculate extends PiMessage

case class Work(start: Int, nrOfElements: Int) extends PiMessage

case class Result(value: Double) extends PiMessage

Creating the worker

Now we can create the worker actor. Create a new class called Worker as before. We need to mix in the Actor trait and defining the receive method. The receive method defines our message handler. We expect it to be able to handle the Work message so we need to add a handler for this message:

class Worker extends Actor {

def receive = {

case Work(start, nrOfElements) =>

self reply Result(calculatePiFor(start, nrOfElements)) // perform the work

}

}

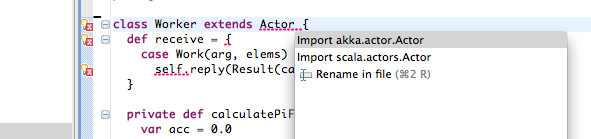

The Actor trait is defined in akka.actor and you can either import it explicitly, or let Eclipse do it for you when it cannot resolve the Actor trait. The quick fix option (Ctrl-F1) will offer two options:

Choose the Akka Actor and move on.

As you can see we have now created an Actor with a receive method as a handler for the Work message. In this handler we invoke the calculatePiFor(..) method, wrap the result in a Result message and send it back to the original sender using self.reply. In Akka the sender reference is implicitly passed along with the message so that the receiver can always reply or store away the sender reference for future use.

The only thing missing in our Worker actor is the implementation on the calculatePiFor(..) method. While there are many ways we can implement this algorithm in Scala, in this introductory tutorial we have chosen an imperative style using a for comprehension and an accumulator:

def calculatePiFor(start: Int, nrOfElements: Int): Double = {

var acc = 0.0

for (i <- start until (start + nrOfElements))

acc += 4.0 * (1 - (i % 2) * 2) / (2 * i + 1)

acc

}

Creating the master

Now create a new class for the master actor. The master actor is a little bit more involved. In its constructor we need to create the workers (the Worker actors) and start them. We will also wrap them in a load-balancing router to make it easier to spread out the work evenly between the workers. First we need to add some imports:

import akka.actor.{Actor, PoisonPill}

import akka.routing.{Routing, CyclicIterator}

import Routing._

import akka.dispatch.Dispatchers

import java.util.concurrent.CountDownLatch

and then we can create the workers:

// create the workers

val workers = Vector.fill(nrOfWorkers)(actorOf[Worker].start())

// wrap them with a load-balancing router

val router = Routing.loadBalancerActor(CyclicIterator(workers)).start()

As you can see we are using the actorOf factory method to create actors, this method returns as an ActorRef which is a reference to our newly created actor. This method is available in the Actor object but is usually imported:

import akka.actor.Actor.actorOf

There are two versions of actorOf; one of them taking a actor type and the other one an instance of an actor. The former one (actorOf[MyActor]) is used when the actor class has a no-argument constructor while the second one (actorOf(new MyActor(..))) is used when the actor class has a constructor that takes arguments. This is the only way to create an instance of an Actor and the actorOf method ensures this. The latter version is using call-by-name and lazily creates the actor within the scope of the actorOf method. The actorOf method instantiates the actor and returns, not an instance to the actor, but an instance to an ActorRef. This reference is the handle through which you communicate with the actor. It is immutable, serializable and location-aware meaning that it “remembers” its original actor even if it is sent to other nodes across the network and can be seen as the equivalent to the Erlang actor’s PID.

The actor’s life-cycle is:

- Created – Actor.actorOf[MyActor] – can not receive messages

- Started – actorRef.start() – can receive messages

- Stopped – actorRef.stop() – can not receive messages

Once the actor has been stopped it is dead and can not be started again.

Now we have a router that is representing all our workers in a single abstraction. If you paid attention to the code above, you saw that we were using the nrOfWorkers variable. This variable and others we have to pass to the Master actor in its constructor. So now let’s create the master actor. We have to pass in three integer variables:

- nrOfWorkers – defining how many workers we should start up

- nrOfMessages – defining how many number chunks to send out to the workers

- nrOfElements – defining how big the number chunks sent to each worker should be

Here is the master actor:

class Master(

nrOfWorkers: Int, nrOfMessages: Int, nrOfElements: Int, latch: CountDownLatch)

extends Actor {

var pi: Double = _

var nrOfResults: Int = _

var start: Long = _

// create the workers

val workers = Vector.fill(nrOfWorkers)(actorOf[Worker].start())

// wrap them with a load-balancing router

val router = Routing.loadBalancerActor(CyclicIterator(workers)).start()

def receive = { ... }

override def preStart() {

start = System.currentTimeMillis

}

override def postStop() {

// tell the world that the calculation is complete

println(

"\n\tPi estimate: \t\t%s\n\tCalculation time: \t%s millis"

.format(pi, (System.currentTimeMillis - start)))

latch.countDown()

}

}

A couple of things are worth explaining further.

First, we are passing in a java.util.concurrent.CountDownLatch to the Master actor. This latch is only used for plumbing (in this specific tutorial), to have a simple way of letting the outside world knowing when the master can deliver the result and shut down. In more idiomatic Akka code, as we will see in part two of this tutorial series, we would not use a latch but other abstractions and functions like Channel, Future and ? to achieve the same thing in a non-blocking way. But for simplicity let’s stick to a CountDownLatch for now.

Second, we are adding a couple of life-cycle callback methods; preStart and postStop. In the preStart callback we are recording the time when the actor is started and in the postStop callback we are printing out the result (the approximation of Pi) and the time it took to calculate it. In this call we also invoke latch.countDown to tell the outside world that we are done.

But we are not done yet. We are missing the message handler for the Master actor. This message handler needs to be able to react to two different messages:

- Calculate – which should start the calculation

- Result – which should aggregate the different results

The Calculate handler is sending out work to all the Worker actors and after doing that it also sends a Broadcast(PoisonPill) message to the router, which will send out the PoisonPill message to all the actors it is representing (in our case all the Worker actors). PoisonPill is a special kind of message that tells the receiver to shut itself down using the normal shutdown method; self.stop. We also send a PoisonPill to the router itself (since it’s also an actor that we want to shut down).

The Result handler is simpler, here we get the value from the Result message and aggregate it to our pi member variable. We also keep track of how many results we have received back, and if that matches the number of tasks sent out, the Master actor considers itself done and shuts down.

Let’s capture this in code:

// message handler

def receive = {

case Calculate =>

// schedule work

for (i <- 0 until nrOfMessages) router ! Work(i * nrOfElements, nrOfElements)

// send a PoisonPill to all workers telling them to shut down themselves

router ! Broadcast(PoisonPill)

// send a PoisonPill to the router, telling him to shut himself down

router ! PoisonPill

case Result(value) =>

// handle result from the worker

pi += value

nrOfResults += 1

if (nrOfResults == nrOfMessages) self.stop()

}

Bootstrap the calculation

Now the only thing that is left to implement is the runner that should bootstrap and run the calculation for us. We do that by creating an object that we call Pi, here we can extend the App trait in Scala, which means that we will be able to run this as an application directly from the command line or using the Eclipse Runner.

The Pi object is a perfect container module for our actors and messages, so let’s put them all there. We also create a method calculate in which we start up the Master actor and wait for it to finish:

object Pi extends App {

calculate(nrOfWorkers = 4, nrOfElements = 10000, nrOfMessages = 10000)

... // actors and messages

def calculate(nrOfWorkers: Int, nrOfElements: Int, nrOfMessages: Int) {

// this latch is only plumbing to know when the calculation is completed

val latch = new CountDownLatch(1)

// create the master

val master = actorOf(

new Master(nrOfWorkers, nrOfMessages, nrOfElements, latch)).start()

// start the calculation

master ! Calculate

// wait for master to shut down

latch.await()

}

}

That’s it. Now we are done.

Run it from Eclipse

Eclipse builds your project on every save when Project/Build Automatically is set. If not, bring you project up to date by clicking Project/Build Project. If there are no compilation errors, you can right-click in the editor where Pi is defined, and choose Run as.. /Scala application. If everything works fine, you should see:

AKKA_HOME is defined as [/Users/jboner/tools/akka-actors-1.3.1]

loading config from [/Users/jboner/tools/akka-actors-1.3.1/config/akka.conf].

Pi estimate: 3.1435501812459323

Calculation time: 858 millis

If you have not defined an the AKKA_HOME environment variable then Akka can’t find the akka.conf configuration file and will print out a Can’t load akka.conf warning. This is ok since it will then just use the defaults.

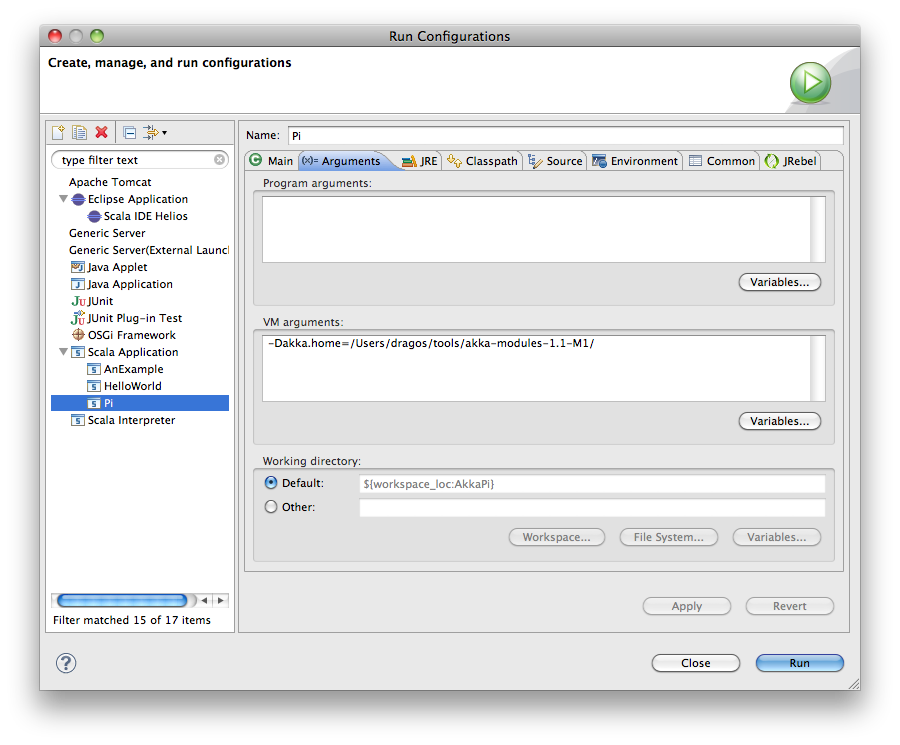

You can also define a new Run configuration, by going to Run/Run Configurations. Create a new Scala application and choose the tutorial project and the main class to be akkatutorial.Pi. You can pass additional command line arguments to the JVM on the Arguments page, for instance to define where akka.conf is:

Once you finished your run configuration, click Run. You should see the same output in the Console window. You can use the same configuration for debugging the application, by choosing Run/Debug History or just Debug As.

Conclusion

We have learned how to create our first Akka project using Akka’s actors to speed up a computation-intensive problem by scaling out on multi-core processors (also known as scaling up). We have also learned to compile and run an Akka project using Eclipse.

If you have a multi-core machine then I encourage you to try out different number of workers (number of working actors) by tweaking the nrOfWorkers variable to for example; 2, 4, 6, 8 etc. to see performance improvement by scaling up.

Now we are ready to take on more advanced problems. In the next tutorial we will build on this one, refactor it into more idiomatic Akka and Scala code, and introduce a few new concepts and abstractions. Whenever you feel ready, join me in the Getting Started Tutorial: Second Chapter.

Happy hakking.

Contents