Actors

The Actor Model provides a higher level of abstraction for writing concurrent and distributed systems. It alleviates the developer from having to deal with explicit locking and thread management, making it easier to write correct concurrent and parallel systems. Actors were defined in the 1973 paper by Carl Hewitt but have been popularized by the Erlang language, and used for example at Ericsson with great success to build highly concurrent and reliable telecom systems.

The API of Akka’s Actors is similar to Scala Actors which has borrowed some of its syntax from Erlang.

Creating Actors

Note

Since Akka enforces parental supervision every actor is supervised and (potentially) the supervisor of its children, it is advisable that you familiarize yourself with Actor Systems and Supervision and Monitoring and it may also help to read Actor References, Paths and Addresses.

Defining an Actor class

Actor classes are implemented by extending the Actor class and implementing the receive method. The receive method should define a series of case statements (which has the type PartialFunction[Any, Unit]) that defines which messages your Actor can handle, using standard Scala pattern matching, along with the implementation of how the messages should be processed.

Here is an example:

import akka.actor.Actor

import akka.actor.Props

import akka.event.Logging

class MyActor extends Actor {

val log = Logging(context.system, this)

def receive = {

case "test" ⇒ log.info("received test")

case _ ⇒ log.info("received unknown message")

}

}

Please note that the Akka Actor receive message loop is exhaustive, which is different compared to Erlang and the late Scala Actors. This means that you need to provide a pattern match for all messages that it can accept and if you want to be able to handle unknown messages then you need to have a default case as in the example above. Otherwise an akka.actor.UnhandledMessage(message, sender, recipient) will be published to the ActorSystem's EventStream.

Note further that the return type of the behavior defined above is Unit; if the actor shall reply to the received message then this must be done explicitly as explained below.

The result of the receive method is a partial function object, which is stored within the actor as its “initial behavior”, see Become/Unbecome for further information on changing the behavior of an actor after its construction.

Props

Props is a configuration class to specify options for the creation of actors, think of it as an immutable and thus freely shareable recipe for creating an actor including associated deployment information (e.g. which dispatcher to use, see more below). Here are some examples of how to create a Props instance.

import akka.actor.Props

val props1 = Props[MyActor]

val props3 = Props(classOf[ActorWithArgs], "arg")

The last line shows how to pass constructor arguments to the Actor being created. The presence of a matching constructor is verified during construction of the Props object, resulting in an IllegalArgumentEception if no or multiple matching constructors are found.

Deprecated Variants

Up to Akka 2.1 there were also the following possibilities (which are retained for a migration period):

// DEPRECATED: old case class signature

val props4 = Props(

creator = { () ⇒ new MyActor },

dispatcher = "my-dispatcher")

// DEPRECATED due to duplicate functionality with Props.apply()

val props5 = props1.withCreator(new MyActor)

// DEPRECATED due to duplicate functionality with Props.apply()

val props6 = props1.withCreator(classOf[MyActor])

// NOT RECOMMENDED: encourages to close over enclosing class

val props7 = Props(new MyActor)

The first one is deprecated because the case class structure changed between Akka 2.1 and 2.2.

The two variants in the middle are deprecated because Props are primarily concerned with actor creation and thus the “creator” part should be explicitly set when creating an instance. In case you want to deploy one actor in the same was as another, simply use Props(...).withDeploy(otherProps.deploy).

The last one is not technically deprecated, but it is not recommended because it encourages to close over the enclosing scope, resulting in non-serializable Props and possibly race conditions (breaking the actor encapsulation). We will provide a macro-based solution in a future release which allows similar syntax without the headaches, at which point this variant will be properly deprecated.

There were two use-cases for these methods: passing constructor arguments to the actor—which is solved by the newly introduced Props.apply(clazz, args) method above—and creating actors “on the spot” as anonymous classes. The latter should be solved by making these actors named inner classes instead (if they are not declared within a top-level object then the enclosing instance’s this reference needs to be passed as the first argument).

Warning

Declaring one actor within another is very dangerous and breaks actor encapsulation. Never pass an actor’s this reference into Props!

Recommended Practices

It is a good idea to provide factory methods on the companion object of each Actor which help keeping the creation of suitable Props as close to the actor definition as possible, thus containing the gap in type-safety introduced by reflective instantiation within a single class instead of spreading it out across a whole code-base. This helps especially when refactoring the actor’s constructor signature at a later point, where compiler checks will allow this modification to be done with greater confidence than without.

object DemoActor {

/**

* Create Props for an actor of this type.

* @param name The name to be passed to this actor’s constructor.

* @return a Props for creating this actor, which can then be further configured

* (e.g. calling `.withDispatcher()` on it)

*/

def props(name: String): Props = Props(classOf[DemoActor], name)

}

class DemoActor(name: String) extends Actor {

def receive = {

case x ⇒ // some behavior

}

}

// ...

context.actorOf(DemoActor.props("hello"))

Creating Actors with Props

Actors are created by passing a Props instance into the actorOf factory method which is available on ActorSystem and ActorContext.

import akka.actor.ActorSystem

// ActorSystem is a heavy object: create only one per application

val system = ActorSystem("mySystem")

val myActor = system.actorOf(Props[MyActor], "myactor2")

Using the ActorSystem will create top-level actors, supervised by the actor system’s provided guardian actor, while using an actor’s context will create a child actor.

class FirstActor extends Actor {

val child = context.actorOf(Props[MyActor], name = "myChild")

// plus some behavior ...

}

It is recommended to create a hierarchy of children, grand-children and so on such that it fits the logical failure-handling structure of the application, see Actor Systems.

The call to actorOf returns an instance of ActorRef. This is a handle to the actor instance and the only way to interact with it. The ActorRef is immutable and has a one to one relationship with the Actor it represents. The ActorRef is also serializable and network-aware. This means that you can serialize it, send it over the wire and use it on a remote host and it will still be representing the same Actor on the original node, across the network.

The name parameter is optional, but you should preferably name your actors, since that is used in log messages and for identifying actors. The name must not be empty or start with $, but it may contain URL encoded characters (eg. %20 for a blank space). If the given name is already in use by another child to the same parent an InvalidActorNameException is thrown.

Actors are automatically started asynchronously when created.

Dependency Injection

If your Actor has a constructor that takes parameters then those need to be part of the Props as well, as described above. But there are cases when a factory method must be used, for example when the actual constructor arguments are determined by a dependency injection framework.

import akka.actor.IndirectActorProducer

class DependencyInjector(applicationContext: AnyRef, beanName: String)

extends IndirectActorProducer {

override def actorClass = classOf[Actor]

override def produce =

// obtain fresh Actor instance from DI framework ...

}

val actorRef = system.actorOf(

Props(classOf[DependencyInjector], applicationContext, "hello"),

"helloBean")

Warning

You might be tempted at times to offer an IndirectActorProducer which always returns the same instance, e.g. by using a lazy val. This is not supported, as it goes against the meaning of an actor restart, which is described here: What Restarting Means.

When using a dependency injection framework, actor beans MUST NOT have singleton scope.

Techniques for dependency injection and integration with dependency injection frameworks are described in more depth in the Using Akka with Dependency Injection guideline and the Akka Java Spring tutorial in Typesafe Activator.

The Actor DSL

Simple actors—for example one-off workers or even when trying things out in the REPL—can be created more concisely using the Act trait. The supporting infrastructure is bundled in the following import:

import akka.actor.ActorDSL._

import akka.actor.ActorSystem

implicit val system = ActorSystem("demo")

This import is assumed for all code samples throughout this section. The implicit actor system serves as ActorRefFactory for all examples below. To define a simple actor, the following is sufficient:

val a = actor(new Act {

become {

case "hello" ⇒ sender ! "hi"

}

})

Here, actor takes the role of either system.actorOf or context.actorOf, depending on which context it is called in: it takes an implicit ActorRefFactory, which within an actor is available in the form of the implicit val context: ActorContext. Outside of an actor, you’ll have to either declare an implicit ActorSystem, or you can give the factory explicitly (see further below).

The two possible ways of issuing a context.become (replacing or adding the new behavior) are offered separately to enable a clutter-free notation of nested receives:

val a = actor(new Act {

become { // this will replace the initial (empty) behavior

case "info" ⇒ sender ! "A"

case "switch" ⇒

becomeStacked { // this will stack upon the "A" behavior

case "info" ⇒ sender ! "B"

case "switch" ⇒ unbecome() // return to the "A" behavior

}

case "lobotomize" ⇒ unbecome() // OH NOES: Actor.emptyBehavior

}

})

Please note that calling unbecome more often than becomeStacked results in the original behavior being installed, which in case of the Act trait is the empty behavior (the outer become just replaces it during construction).

Life-cycle hooks are also exposed as DSL elements (see Start Hook and Stop Hook below), where later invocations of the methods shown below will replace the contents of the respective hooks:

val a = actor(new Act {

whenStarting { testActor ! "started" }

whenStopping { testActor ! "stopped" }

})

The above is enough if the logical life-cycle of the actor matches the restart cycles (i.e. whenStopping is executed before a restart and whenStarting afterwards). If that is not desired, use the following two hooks (see Restart Hooks below):

val a = actor(new Act {

become {

case "die" ⇒ throw new Exception

}

whenFailing { case m @ (cause, msg) ⇒ testActor ! m }

whenRestarted { cause ⇒ testActor ! cause }

})

It is also possible to create nested actors, i.e. grand-children, like this:

// here we pass in the ActorRefFactory explicitly as an example

val a = actor(system, "fred")(new Act {

val b = actor("barney")(new Act {

whenStarting { context.parent ! ("hello from " + self.path) }

})

become {

case x ⇒ testActor ! x

}

})

Note

In some cases it will be necessary to explicitly pass the ActorRefFactory to the actor method (you will notice when the compiler tells you about ambiguous implicits).

The grand-child will be supervised by the child; the supervisor strategy for this relationship can also be configured using a DSL element (supervision directives are part of the Act trait):

superviseWith(OneForOneStrategy() {

case e: Exception if e.getMessage == "hello" ⇒ Stop

case _: Exception ⇒ Resume

})

Last but not least there is a little bit of convenience magic built-in, which detects if the runtime class of the statically given actor subtype extends the RequiresMessageQueue trait via the Stash trait (this is a complicated way of saying that new Act with Stash would not work because its runtime erased type is just an anonymous subtype of Act). The purpose is to automatically use the appropriate deque-based mailbox type required by Stash. If you want to use this magic, simply extend ActWithStash:

val a = actor(new ActWithStash {

become {

case 1 ⇒ stash()

case 2 ⇒

testActor ! 2; unstashAll(); becomeStacked {

case 1 ⇒ testActor ! 1; unbecome()

}

}

})

The Inbox

When writing code outside of actors which shall communicate with actors, the ask pattern can be a solution (see below), but there are two thing it cannot do: receiving multiple replies (e.g. by subscribing an ActorRef to a notification service) and watching other actors’ lifecycle. For these purposes there is the Inbox class:

implicit val i = inbox()

echo ! "hello"

i.receive() must be("hello")

There is an implicit conversion from inbox to actor reference which means that in this example the sender reference will be that of the actor hidden away within the inbox. This allows the reply to be received on the last line. Watching an actor is quite simple as well:

val target = // some actor

val i = inbox()

i watch target

Actor API

The Actor trait defines only one abstract method, the above mentioned receive, which implements the behavior of the actor.

If the current actor behavior does not match a received message, unhandled is called, which by default publishes an akka.actor.UnhandledMessage(message, sender, recipient) on the actor system’s event stream (set configuration item akka.actor.debug.unhandled to on to have them converted into actual Debug messages).

In addition, it offers:

self reference to the ActorRef of the actor

sender reference sender Actor of the last received message, typically used as described in Reply to messages

supervisorStrategy user overridable definition the strategy to use for supervising child actors

This strategy is typically declared inside the actor in order to have access to the actor’s internal state within the decider function: since failure is communicated as a message sent to the supervisor and processed like other messages (albeit outside of the normal behavior), all values and variables within the actor are available, as is the sender reference (which will be the immediate child reporting the failure; if the original failure occurred within a distant descendant it is still reported one level up at a time).

context exposes contextual information for the actor and the current message, such as:

- factory methods to create child actors (actorOf)

- system that the actor belongs to

- parent supervisor

- supervised children

- lifecycle monitoring

- hotswap behavior stack as described in Become/Unbecome

You can import the members in the context to avoid prefixing access with context.

class FirstActor extends Actor {

import context._

val myActor = actorOf(Props[MyActor], name = "myactor")

def receive = {

case x ⇒ myActor ! x

}

}

The remaining visible methods are user-overridable life-cycle hooks which are described in the following:

def preStart(): Unit = ()

def postStop(): Unit = ()

def preRestart(reason: Throwable, message: Option[Any]): Unit = {

context.children foreach { child ⇒

context.unwatch(child)

context.stop(child)

}

postStop()

}

def postRestart(reason: Throwable): Unit = {

preStart()

}

The implementations shown above are the defaults provided by the Actor trait.

Actor Lifecycle

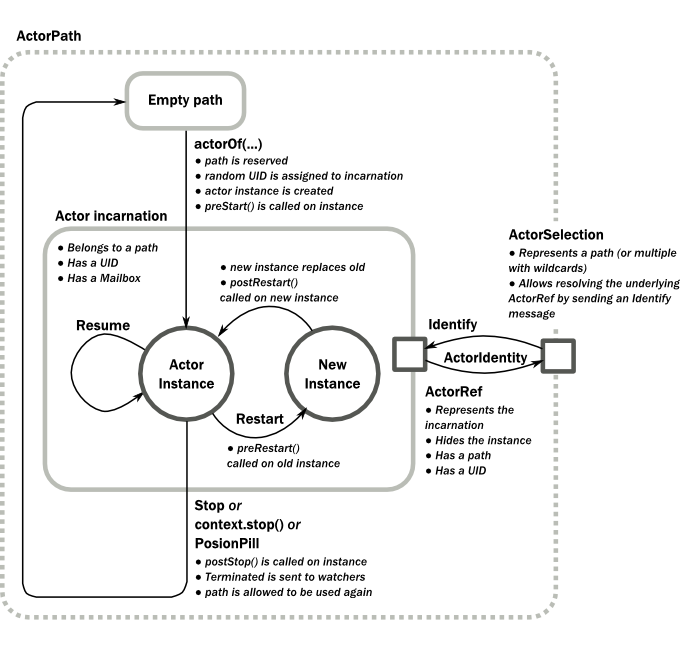

A path in an actor system represents a "place" which might be occupied by a living actor. Initially (apart from system initialized actors) a path is empty. When actorOf() is called it assigns an incarnation of the actor described by the passed Props to the given path. An actor incarnation is identified by the path and a UID. A restart only swaps the Actor instance defined by the Props but the incarnation and hence the UID remains the same.

The lifecycle of an incarnation ends when the actor is stopped. At that point the appropriate lifecycle events are called and watching actors are notified of the termination. After the incarnation is stopped, the path can be reused again by creating an actor with actorOf(). In this case the name of the new incarnation will be the same as the previous one but the UIDs will differ.

An ActorRef always represents an incarnation (path and UID) not just a given path. Therefore if an actor is stopped and a new one with the same name is created an ActorRef of the old incarnation will not point to the new one.

ActorSelection on the other hand points to the path (or multiple paths if wildcards are used) and is completely oblivious to which incarnation is currently occupying it. ActorSelection cannot be watched for this reason. It is possible to resolve the current incarnation's ActorRef living under the path by sending an Identify message to the ActorSelection which will be replied to with an ActorIdentity containing the correct reference (see Identifying Actors via Actor Selection). This can also be done with the resolveOne method of the ActorSelection, which returns a Future of the matching ActorRef.

Lifecycle Monitoring aka DeathWatch

In order to be notified when another actor terminates (i.e. stops permanently, not temporary failure and restart), an actor may register itself for reception of the Terminated message dispatched by the other actor upon termination (see Stopping Actors). This service is provided by the DeathWatch component of the actor system.

Registering a monitor is easy:

import akka.actor.{ Actor, Props, Terminated }

class WatchActor extends Actor {

val child = context.actorOf(Props.empty, "child")

context.watch(child) // <-- this is the only call needed for registration

var lastSender = system.deadLetters

def receive = {

case "kill" ⇒

context.stop(child); lastSender = sender

case Terminated(`child`) ⇒ lastSender ! "finished"

}

}

It should be noted that the Terminated message is generated independent of the order in which registration and termination occur. In particular, the watching actor will receive a Terminated message even if the watched actor has already been terminated at the time of registration.

Registering multiple times does not necessarily lead to multiple messages being generated, but there is no guarantee that only exactly one such message is received: if termination of the watched actor has generated and queued the message, and another registration is done before this message has been processed, then a second message will be queued, because registering for monitoring of an already terminated actor leads to the immediate generation of the Terminated message.

It is also possible to deregister from watching another actor’s liveliness using context.unwatch(target). This works even if the Terminated message has already been enqueued in the mailbox; after calling unwatch no Terminated message for that actor will be processed anymore.

Start Hook

Right after starting the actor, its preStart method is invoked.

override def preStart() {

child = context.actorOf(Props[MyActor], "child")

}

This method is called when the actor is first created. During restarts it is called by the default implementation of postRestart, which means that by overriding that method you can choose whether the initialization code in this method is called only exactly once for this actor or for every restart. Initialization code which is part of the actor’s constructor will always be called when an instance of the actor class is created, which happens at every restart.

Restart Hooks

All actors are supervised, i.e. linked to another actor with a fault handling strategy. Actors may be restarted in case an exception is thrown while processing a message (see Supervision and Monitoring). This restart involves the hooks mentioned above:

The old actor is informed by calling preRestart with the exception which caused the restart and the message which triggered that exception; the latter may be None if the restart was not caused by processing a message, e.g. when a supervisor does not trap the exception and is restarted in turn by its supervisor, or if an actor is restarted due to a sibling’s failure. If the message is available, then that message’s sender is also accessible in the usual way (i.e. by calling sender).

This method is the best place for cleaning up, preparing hand-over to the fresh actor instance, etc. By default it stops all children and calls postStop.

The initial factory from the actorOf call is used to produce the fresh instance.

The new actor’s postRestart method is invoked with the exception which caused the restart. By default the preStart is called, just as in the normal start-up case.

An actor restart replaces only the actual actor object; the contents of the mailbox is unaffected by the restart, so processing of messages will resume after the postRestart hook returns. The message that triggered the exception will not be received again. Any message sent to an actor while it is being restarted will be queued to its mailbox as usual.

Warning

Be aware that the ordering of failure notifications relative to user messages is not deterministic. In particular, a parent might restart its child before it has processed the last messages sent by the child before the failure. See Discussion: Message Ordering for details.

Stop Hook

After stopping an actor, its postStop hook is called, which may be used e.g. for deregistering this actor from other services. This hook is guaranteed to run after message queuing has been disabled for this actor, i.e. messages sent to a stopped actor will be redirected to the deadLetters of the ActorSystem.

Identifying Actors via Actor Selection

As described in Actor References, Paths and Addresses, each actor has a unique logical path, which is obtained by following the chain of actors from child to parent until reaching the root of the actor system, and it has a physical path, which may differ if the supervision chain includes any remote supervisors. These paths are used by the system to look up actors, e.g. when a remote message is received and the recipient is searched, but they are also useful more directly: actors may look up other actors by specifying absolute or relative paths—logical or physical—and receive back an ActorSelection with the result:

// will look up this absolute path

context.actorSelection("/user/serviceA/aggregator")

// will look up sibling beneath same supervisor

context.actorSelection("../joe")

The supplied path is parsed as a java.net.URI, which basically means that it is split on / into path elements. If the path starts with /, it is absolute and the look-up starts at the root guardian (which is the parent of "/user"); otherwise it starts at the current actor. If a path element equals .., the look-up will take a step “up” towards the supervisor of the currently traversed actor, otherwise it will step “down” to the named child. It should be noted that the .. in actor paths here always means the logical structure, i.e. the supervisor.

The path elements of an actor selection may contain wildcard patterns allowing for broadcasting of messages to that section:

// will look all children to serviceB with names starting with worker

context.actorSelection("/user/serviceB/worker*")

// will look up all siblings beneath same supervisor

context.actorSelection("../*")

Messages can be sent via the ActorSelection and the path of the ActorSelection is looked up when delivering each message. If the selection does not match any actors the message will be dropped.

To acquire an ActorRef for an ActorSelection you need to send a message to the selection and use the sender reference of the reply from the actor. There is a built-in Identify message that all Actors will understand and automatically reply to with a ActorIdentity message containing the ActorRef. This message is handled specially by the actors which are traversed in the sense that if a concrete name lookup fails (i.e. a non-wildcard path element does not correspond to a live actor) then a negative result is generated. Please note that this does not mean that delivery of that reply is guaranteed, it still is a normal message.

import akka.actor.{ Actor, Props, Identify, ActorIdentity, Terminated }

class Follower extends Actor {

val identifyId = 1

context.actorSelection("/user/another") ! Identify(identifyId)

def receive = {

case ActorIdentity(`identifyId`, Some(ref)) ⇒

context.watch(ref)

context.become(active(ref))

case ActorIdentity(`identifyId`, None) ⇒ context.stop(self)

}

def active(another: ActorRef): Actor.Receive = {

case Terminated(`another`) ⇒ context.stop(self)

}

}

You can also acquire an ActorRef for an ActorSelection with the resolveOne method of the ActorSelection. It returns a Future of the matching ActorRef if such an actor exists. It is completed with failure [[akka.actor.ActorNotFound]] if no such actor exists or the identification didn't complete within the supplied timeout.

Remote actor addresses may also be looked up, if remoting is enabled:

context.actorSelection("akka.tcp://app@otherhost:1234/user/serviceB")

An example demonstrating actor look-up is given in Remote Lookup.

Note

actorFor is deprecated in favor of actorSelection because actor references acquired with actorFor behaves different for local and remote actors. In the case of a local actor reference, the named actor needs to exist before the lookup, or else the acquired reference will be an EmptyLocalActorRef. This will be true even if an actor with that exact path is created after acquiring the actor reference. For remote actor references acquired with actorFor the behaviour is different and sending messages to such a reference will under the hood look up the actor by path on the remote system for every message send.

Messages and immutability

IMPORTANT: Messages can be any kind of object but have to be immutable. Scala can’t enforce immutability (yet) so this has to be by convention. Primitives like String, Int, Boolean are always immutable. Apart from these the recommended approach is to use Scala case classes which are immutable (if you don’t explicitly expose the state) and works great with pattern matching at the receiver side.

Here is an example:

// define the case class

case class Register(user: User)

// create a new case class message

val message = Register(user)

Send messages

Messages are sent to an Actor through one of the following methods.

- ! means “fire-and-forget”, e.g. send a message asynchronously and return immediately. Also known as tell.

- ? sends a message asynchronously and returns a Future representing a possible reply. Also known as ask.

Message ordering is guaranteed on a per-sender basis.

Note

There are performance implications of using ask since something needs to keep track of when it times out, there needs to be something that bridges a Promise into an ActorRef and it also needs to be reachable through remoting. So always prefer tell for performance, and only ask if you must.

Tell: Fire-forget

This is the preferred way of sending messages. No blocking waiting for a message. This gives the best concurrency and scalability characteristics.

actorRef ! message

If invoked from within an Actor, then the sending actor reference will be implicitly passed along with the message and available to the receiving Actor in its sender: ActorRef member field. The target actor can use this to reply to the original sender, by using sender ! replyMsg.

If invoked from an instance that is not an Actor the sender will be deadLetters actor reference by default.

Ask: Send-And-Receive-Future

The ask pattern involves actors as well as futures, hence it is offered as a use pattern rather than a method on ActorRef:

import akka.pattern.{ ask, pipe }

import system.dispatcher // The ExecutionContext that will be used

case class Result(x: Int, s: String, d: Double)

case object Request

implicit val timeout = Timeout(5 seconds) // needed for `?` below

val f: Future[Result] =

for {

x ← ask(actorA, Request).mapTo[Int] // call pattern directly

s ← (actorB ask Request).mapTo[String] // call by implicit conversion

d ← (actorC ? Request).mapTo[Double] // call by symbolic name

} yield Result(x, s, d)

f pipeTo actorD // .. or ..

pipe(f) to actorD

This example demonstrates ask together with the pipeTo pattern on futures, because this is likely to be a common combination. Please note that all of the above is completely non-blocking and asynchronous: ask produces a Future, three of which are composed into a new future using the for-comprehension and then pipeTo installs an onComplete-handler on the future to affect the submission of the aggregated Result to another actor.

Using ask will send a message to the receiving Actor as with tell, and the receiving actor must reply with sender ! reply in order to complete the returned Future with a value. The ask operation involves creating an internal actor for handling this reply, which needs to have a timeout after which it is destroyed in order not to leak resources; see more below.

Warning

To complete the future with an exception you need send a Failure message to the sender. This is not done automatically when an actor throws an exception while processing a message.

try {

val result = operation()

sender ! result

} catch {

case e: Exception ⇒

sender ! akka.actor.Status.Failure(e)

throw e

}

If the actor does not complete the future, it will expire after the timeout period, completing it with an AskTimeoutException. The timeout is taken from one of the following locations in order of precedence:

- explicitly given timeout as in:

import scala.concurrent.duration._

import akka.pattern.ask

val future = myActor.ask("hello")(5 seconds)

- implicit argument of type akka.util.Timeout, e.g.

import scala.concurrent.duration._

import akka.util.Timeout

import akka.pattern.ask

implicit val timeout = Timeout(5 seconds)

val future = myActor ? "hello"

See Futures for more information on how to await or query a future.

The onComplete, onSuccess, or onFailure methods of the Future can be used to register a callback to get a notification when the Future completes. Gives you a way to avoid blocking.

Warning

When using future callbacks, such as onComplete, onSuccess, and onFailure, inside actors you need to carefully avoid closing over the containing actor’s reference, i.e. do not call methods or access mutable state on the enclosing actor from within the callback. This would break the actor encapsulation and may introduce synchronization bugs and race conditions because the callback will be scheduled concurrently to the enclosing actor. Unfortunately there is not yet a way to detect these illegal accesses at compile time. See also: Actors and shared mutable state

Forward message

You can forward a message from one actor to another. This means that the original sender address/reference is maintained even though the message is going through a 'mediator'. This can be useful when writing actors that work as routers, load-balancers, replicators etc.

target forward message

Receive messages

An Actor has to implement the receive method to receive messages:

type Receive = PartialFunction[Any, Unit]

def receive: Actor.Receive

This method returns a PartialFunction, e.g. a ‘match/case’ clause in which the message can be matched against the different case clauses using Scala pattern matching. Here is an example:

import akka.actor.Actor

import akka.actor.Props

import akka.event.Logging

class MyActor extends Actor {

val log = Logging(context.system, this)

def receive = {

case "test" ⇒ log.info("received test")

case _ ⇒ log.info("received unknown message")

}

}

Reply to messages

If you want to have a handle for replying to a message, you can use sender, which gives you an ActorRef. You can reply by sending to that ActorRef with sender ! replyMsg. You can also store the ActorRef for replying later, or passing on to other actors. If there is no sender (a message was sent without an actor or future context) then the sender defaults to a 'dead-letter' actor ref.

case request =>

val result = process(request)

sender ! result // will have dead-letter actor as default

Receive timeout

The ActorContext setReceiveTimeout defines the inactivity timeout after which the sending of a ReceiveTimeout message is triggered. When specified, the receive function should be able to handle an akka.actor.ReceiveTimeout message. 1 millisecond is the minimum supported timeout.

Please note that the receive timeout might fire and enqueue the ReceiveTimeout message right after another message was enqueued; hence it is not guaranteed that upon reception of the receive timeout there must have been an idle period beforehand as configured via this method.

Once set, the receive timeout stays in effect (i.e. continues firing repeatedly after inactivity periods). Pass in Duration.Undefined to switch off this feature.

import akka.actor.ReceiveTimeout

import scala.concurrent.duration._

class MyActor extends Actor {

// To set an initial delay

context.setReceiveTimeout(30 milliseconds)

def receive = {

case "Hello" ⇒

// To set in a response to a message

context.setReceiveTimeout(100 milliseconds)

case ReceiveTimeout ⇒

// To turn it off

context.setReceiveTimeout(Duration.Undefined)

throw new RuntimeException("Receive timed out")

}

}

Stopping actors

Actors are stopped by invoking the stop method of a ActorRefFactory, i.e. ActorContext or ActorSystem. Typically the context is used for stopping child actors and the system for stopping top level actors. The actual termination of the actor is performed asynchronously, i.e. stop may return before the actor is stopped.

Processing of the current message, if any, will continue before the actor is stopped, but additional messages in the mailbox will not be processed. By default these messages are sent to the deadLetters of the ActorSystem, but that depends on the mailbox implementation.

Termination of an actor proceeds in two steps: first the actor suspends its mailbox processing and sends a stop command to all its children, then it keeps processing the internal termination notifications from its children until the last one is gone, finally terminating itself (invoking postStop, dumping mailbox, publishing Terminated on the DeathWatch, telling its supervisor). This procedure ensures that actor system sub-trees terminate in an orderly fashion, propagating the stop command to the leaves and collecting their confirmation back to the stopped supervisor. If one of the actors does not respond (i.e. processing a message for extended periods of time and therefore not receiving the stop command), this whole process will be stuck.

Upon ActorSystem.shutdown, the system guardian actors will be stopped, and the aforementioned process will ensure proper termination of the whole system.

The postStop hook is invoked after an actor is fully stopped. This enables cleaning up of resources:

override def postStop() {

// clean up some resources ...

}

Note

Since stopping an actor is asynchronous, you cannot immediately reuse the name of the child you just stopped; this will result in an InvalidActorNameException. Instead, watch the terminating actor and create its replacement in response to the Terminated message which will eventually arrive.

PoisonPill

You can also send an actor the akka.actor.PoisonPill message, which will stop the actor when the message is processed. PoisonPill is enqueued as ordinary messages and will be handled after messages that were already queued in the mailbox.

Graceful Stop

gracefulStop is useful if you need to wait for termination or compose ordered termination of several actors:

import akka.pattern.gracefulStop

import scala.concurrent.Await

try {

val stopped: Future[Boolean] = gracefulStop(actorRef, 5 seconds)

Await.result(stopped, 6 seconds)

// the actor has been stopped

} catch {

// the actor wasn't stopped within 5 seconds

case e: akka.pattern.AskTimeoutException ⇒

}

When gracefulStop() returns successfully, the actor’s postStop() hook will have been executed: there exists a happens-before edge between the end of postStop() and the return of gracefulStop().

Warning

Keep in mind that an actor stopping and its name being deregistered are separate events which happen asynchronously from each other. Therefore it may be that you will find the name still in use after gracefulStop() returned. In order to guarantee proper deregistration, only reuse names from within a supervisor you control and only in response to a Terminated message, i.e. not for top-level actors.

Become/Unbecome

Upgrade

Akka supports hotswapping the Actor’s message loop (e.g. its implementation) at runtime: invoke the context.become method from within the Actor. become takes a PartialFunction[Any, Unit] that implements the new message handler. The hotswapped code is kept in a Stack which can be pushed and popped.

Warning

Please note that the actor will revert to its original behavior when restarted by its Supervisor.

To hotswap the Actor behavior using become:

class HotSwapActor extends Actor {

import context._

def angry: Receive = {

case "foo" ⇒ sender ! "I am already angry?"

case "bar" ⇒ become(happy)

}

def happy: Receive = {

case "bar" ⇒ sender ! "I am already happy :-)"

case "foo" ⇒ become(angry)

}

def receive = {

case "foo" ⇒ become(angry)

case "bar" ⇒ become(happy)

}

}

This variant of the become method is useful for many different things, such as to implement a Finite State Machine (FSM, for an example see Dining Hakkers). It will replace the current behavior (i.e. the top of the behavior stack), which means that you do not use unbecome, instead always the next behavior is explicitly installed.

The other way of using become does not replace but add to the top of the behavior stack. In this case care must be taken to ensure that the number of “pop” operations (i.e. unbecome) matches the number of “push” ones in the long run, otherwise this amounts to a memory leak (which is why this behavior is not the default).

case object Swap

class Swapper extends Actor {

import context._

val log = Logging(system, this)

def receive = {

case Swap ⇒

log.info("Hi")

become({

case Swap ⇒

log.info("Ho")

unbecome() // resets the latest 'become' (just for fun)

}, discardOld = false) // push on top instead of replace

}

}

object SwapperApp extends App {

val system = ActorSystem("SwapperSystem")

val swap = system.actorOf(Props[Swapper], name = "swapper")

swap ! Swap // logs Hi

swap ! Swap // logs Ho

swap ! Swap // logs Hi

swap ! Swap // logs Ho

swap ! Swap // logs Hi

swap ! Swap // logs Ho

}

Encoding Scala Actors nested receives without accidentally leaking memory

See this Unnested receive example.

Stash

The Stash trait enables an actor to temporarily stash away messages that can not or should not be handled using the actor's current behavior. Upon changing the actor's message handler, i.e., right before invoking context.become or context.unbecome, all stashed messages can be "unstashed", thereby prepending them to the actor's mailbox. This way, the stashed messages can be processed in the same order as they have been received originally.

Note

The trait Stash extends the marker trait RequiresMessageQueue[DequeBasedMessageQueueSemantics] which requests the system to automatically choose a deque based mailbox implementation for the actor. If you want more control over the mailbox, see the documentation on mailboxes: Mailboxes.

Here is an example of the Stash in action:

import akka.actor.Stash

class ActorWithProtocol extends Actor with Stash {

def receive = {

case "open" ⇒

unstashAll()

context.become({

case "write" ⇒ // do writing...

case "close" ⇒

unstashAll()

context.unbecome()

case msg ⇒ stash()

}, discardOld = false) // stack on top instead of replacing

case msg ⇒ stash()

}

}

Invoking stash() adds the current message (the message that the actor received last) to the actor's stash. It is typically invoked when handling the default case in the actor's message handler to stash messages that aren't handled by the other cases. It is illegal to stash the same message twice; to do so results in an IllegalStateException being thrown. The stash may also be bounded in which case invoking stash() may lead to a capacity violation, which results in a StashOverflowException. The capacity of the stash can be configured using the stash-capacity setting (an Int) of the dispatcher's configuration.

Invoking unstashAll() enqueues messages from the stash to the actor's mailbox until the capacity of the mailbox (if any) has been reached (note that messages from the stash are prepended to the mailbox). In case a bounded mailbox overflows, a MessageQueueAppendFailedException is thrown. The stash is guaranteed to be empty after calling unstashAll().

The stash is backed by a scala.collection.immutable.Vector. As a result, even a very large number of messages may be stashed without a major impact on performance.

Warning

Note that the Stash trait must be mixed into (a subclass of) the Actor trait before any trait/class that overrides the preRestart callback. This means it's not possible to write Actor with MyActor with Stash if MyActor overrides preRestart.

Note that the stash is part of the ephemeral actor state, unlike the mailbox. Therefore, it should be managed like other parts of the actor's state which have the same property. The Stash trait’s implementation of preRestart will call unstashAll(), which is usually the desired behavior.

Note

If you want to enforce that your actor can only work with an unbounded stash, then you should use the UnboundedStash trait instead.

Killing an Actor

You can kill an actor by sending a Kill message. This will cause the actor to throw a ActorKilledException, triggering a failure. The actor will suspend operation and its supervisor will be asked how to handle the failure, which may mean resuming the actor, restarting it or terminating it completely. See What Supervision Means for more information.

Use Kill like this:

// kill the 'victim' actor

victim ! Kill

Actors and exceptions

It can happen that while a message is being processed by an actor, that some kind of exception is thrown, e.g. a database exception.

What happens to the Message

If an exception is thrown while a message is being processed (i.e. taken out of its mailbox and handed over to the current behavior), then this message will be lost. It is important to understand that it is not put back on the mailbox. So if you want to retry processing of a message, you need to deal with it yourself by catching the exception and retry your flow. Make sure that you put a bound on the number of retries since you don't want a system to livelock (so consuming a lot of cpu cycles without making progress). Another possibility would be to have a look at the PeekMailbox pattern.

What happens to the mailbox

If an exception is thrown while a message is being processed, nothing happens to the mailbox. If the actor is restarted, the same mailbox will be there. So all messages on that mailbox will be there as well.

What happens to the actor

If code within an actor throws an exception, that actor is suspended and the supervision process is started (see Supervision and Monitoring). Depending on the supervisor’s decision the actor is resumed (as if nothing happened), restarted (wiping out its internal state and starting from scratch) or terminated.

Extending Actors using PartialFunction chaining

A bit advanced but very useful way of defining a base message handler and then extend that, either through inheritance or delegation, is to use PartialFunction.orElse chaining.

abstract class GenericActor extends Actor {

// to be defined in subclassing actor

def specificMessageHandler: Receive

// generic message handler

def genericMessageHandler: Receive = {

case event ⇒ printf("generic: %s\n", event)

}

def receive = specificMessageHandler orElse genericMessageHandler

}

class SpecificActor extends GenericActor {

def specificMessageHandler = {

case event: MyMsg ⇒ printf("specific: %s\n", event.subject)

}

}

case class MyMsg(subject: String)

Or:

class PartialFunctionBuilder[A, B] {

import scala.collection.immutable.Vector

// Abbreviate to make code fit

type PF = PartialFunction[A, B]

private var pfsOption: Option[Vector[PF]] = Some(Vector.empty)

private def mapPfs[C](f: Vector[PF] ⇒ (Option[Vector[PF]], C)): C = {

pfsOption.fold(throw new IllegalStateException("Already built"))(f) match {

case (newPfsOption, result) ⇒ {

pfsOption = newPfsOption

result

}

}

}

def +=(pf: PF): Unit =

mapPfs { case pfs ⇒ (Some(pfs :+ pf), ()) }

def result(): PF =

mapPfs { case pfs ⇒ (None, pfs.foldLeft[PF](Map.empty) { _ orElse _ }) }

}

trait ComposableActor extends Actor {

protected lazy val receiveBuilder = new PartialFunctionBuilder[Any, Unit]

final def receive = receiveBuilder.result()

}

trait TheirComposableActor extends ComposableActor {

receiveBuilder += {

case "foo" ⇒ sender ! "foo received"

}

}

class MyComposableActor extends TheirComposableActor {

receiveBuilder += {

case "bar" ⇒ sender ! "bar received"

}

}

Initialization patterns

The rich lifecycle hooks of Actors provide a useful toolkit to implement various initialization patterns. During the lifetime of an ActorRef, an actor can potentially go through several restarts, where the old instance is replaced by a fresh one, invisibly to the outside observer who only sees the ActorRef.

One may think about the new instances as "incarnations". Initialization might be necessary for every incarnation of an actor, but sometimes one needs initialization to happen only at the birth of the first instance when the ActorRef is created. The following sections provide patterns for different initialization needs.

Initialization via constructor

Using the constructor for initialization has various benefits. First of all, it makes it possible to use val fields to store any state that does not change during the life of the actor instance, making the implementation of the actor more robust. The constructor is invoked for every incarnation of the actor, therefore the internals of the actor can always assume that proper initialization happened. This is also the drawback of this approach, as there are cases when one would like to avoid reinitializing internals on restart. For example, it is often useful to preserve child actors across restarts. The following section provides a pattern for this case.

Initialization via preStart

The method preStart() of an actor is only called once directly during the initialization of the first instance, that is, at creation of its ActorRef. In the case of restarts, preStart() is called from postRestart(), therefore if not overridden, preStart() is called on every incarnation. However, overriding postRestart() one can disable this behavior, and ensure that there is only one call to preStart().

One useful usage of this pattern is to disable creation of new ActorRefs for children during restarts. This can be achieved by overriding preRestart():

override def preStart(): Unit = {

// Initialize children here

}

// Overriding postRestart to disable the call to preStart()

// after restarts

override def postRestart(reason: Throwable): Unit = ()

// The default implementation of preRestart() stops all the children

// of the actor. To opt-out from stopping the children, we

// have to override preRestart()

override def preRestart(reason: Throwable, message: Option[Any]): Unit = {

// Keep the call to postStop(), but no stopping of children

postStop()

}

Please note, that the child actors are still restarted, but no new ActorRef is created. One can recursively apply the same principles for the children, ensuring that their preStart() method is called only at the creation of their refs.

For more information see What Restarting Means.

Initialization via message passing

There are cases when it is impossible to pass all the information needed for actor initialization in the constructor, for example in the presence of circular dependencies. In this case the actor should listen for an initialization message, and use become() or a finite state-machine state transition to encode the initialized and uninitialized states of the actor.

var initializeMe: Option[String] = None

override def receive = {

case "init" ⇒

initializeMe = Some("Up and running")

context.become(initialized, discardOld = true)

}

def initialized: Receive = {

case "U OK?" ⇒ initializeMe foreach { sender ! _ }

}

If the actor may receive messages before it has been initialized, a useful tool can be the Stash to save messages until the initialization finishes, and replaying them after the actor became initialized.

Warning

This pattern should be used with care, and applied only when none of the patterns above are applicable. One of the potential issues is that messages might be lost when sent to remote actors. Also, publishing an ActorRef in an uninitialized state might lead to the condition that it receives a user message before the initialization has been done.

Contents